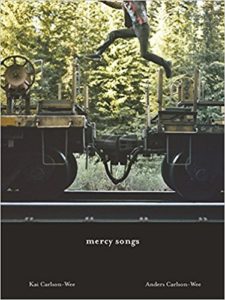

Mercy Songs. Kai Carlson-Wee and Anders Carlson-Wee. Diode Editions, 2016. 31 pgs. $12.00.

Mercy Songs. Kai Carlson-Wee and Anders Carlson-Wee. Diode Editions, 2016. 31 pgs. $12.00.

Mercy Songs is an unusual collaboration between brothers, Kai and Anders Carlson-Wee. The twenty-two poems alternate between the two authors—so it is the collection rather than the poems themselves that is collaborative—but thematically, imagistically, and even stylistically, the poems are closely linked. Many of the poems are composed in comparatively long lines arranged into a single extended stanza. The language is accessible yet sonically attractive. They are set on and around freight trains and railroad tracks, with the first-person speakers not exactly plural but often speaking of (if not as) “we” and poems written by each author referring to “my brother.” The concept and strategy of this chapbook is therefore (I think) unique, but its success depends on what every other collection depends on—the quality of the poems themselves.

The title poem (by Kai) opens with these sentences:

He heard them in the weight room, in the white

expanse of the courtyard covered in snow,

the way it reminded him always of Sundays,

waking up late in the empty apartment at noon,

pulling his socks on, holding a cold can

of Steele Reserve to his chest. He heard them

in the mess hall, in the empty machine shop walls,

the drone of the late-night stations on faith,

the pop of the ping-pong ball in the background,

the gorgeous prayers of Emmanuel Paine

when he really got going, when he drowned out

and slipped into tongue…

The title here, “Mercy Songs,” is crucial to understanding the poem, but what is most impressive is how the imagery becomes so auditory and how the word choice creates auditory impressions for the reader, until the reader begins to hear mercy songs in the language of the poem, just as the speaker hears them in the noises of the day. Many of the poems in this collection rely on alliteration as a primary aural device, the most extended example here being “pop of the ping-pong ball…prayers of Emmanuel Paine.” The poem becomes nearly a litany, but its rhythm and content are both so interesting because of the specificity of the list—“the weight room,” “the mess hall,” “the empty machine shop walls,” “the late night stations on faith,” which is the first overt reference to the religious content of traditional mercy songs. The list continues with items that seem ordinary until we come to “the high-pitched scuff of the bald guard’s boot.” This guard is

…The one who wore crosses

and belted out Lowly, My Savior and Sinnerman

the way Nina Simone had sung it live

at the Winterland Ballroom in ‘75…

The description of this guard occupies the center of the poem, which quickly returns to daily details until we reach the final transcendent sentence:

But mostly, he heard them in the private hours

of waiting to fall asleep, when everyone else was alone

in their dreams and the whole penitentiary seemed

to be floating, like one of those city-sized cruise ships

you take to the Arctic, or Cape of Good Hope,

or those Indian islands with lions and dragons

where pirates had one time divided their treasures

and slept in the mouths of caves.

We don’t absolutely know the setting for the poem until this last sentence, and it is here that readers understand why mercy songs might be so necessary. The speaker experiences this rare moment of privacy as he listens to the night noises while everyone else sleeps. The night is so peaceful that it almost feels free: “the whole penitentiary seemed / to be floating.” The references to lions and dragons and pirates make it seem almost magical until we remember that no, it’s a prison.

Many of the poems in Mercy Songs function this way, surrounding the harsh reality they describe with the pleasurable music of language.

The next poem, “Muscles in Their Throats,” (by Anders) contains a reference near its beginning that directly connects it to “Mercy Songs.” Initially, its content seems quite different from most of the other poems, but as the poem develops, it reveals its true subject: language. Here is the beginning:

The Neanderthals tracked mammoths through the snow.

Postholed twice between each of the creature’s

blue-hued prints. Peered down at the toe digs, hoping

for any fissures in the powder that might be a sign

of weakness. Nightmares larger than the caves

they slept in.

As soon as we reach that fifth sentence, we recognize that the two poems are connected, though not as obviously as the repeated reference to sleeping in caves might suggest. “Muscles in Their Throats” is not about imprisonment, though it may be about mercy. The speaker imagines these Neanderthals hunting, cooking, and eating, likely eating together, but “we don’t know for certain how much they could say / to each other.” Could they speak? Did they have language? In this, perhaps they are radically different from modern humans. But no, the poem suggests:

…It’s no different now. My brother

strips boughs off the wind-stunted pines at treeline

and stacks them on a boulder…

Our resemblance to Neanderthals doesn’t depend on their hypothetical ability to use language. Rather, our language does not solve our inability to communicate, even with someone as close as a brother. The middle third of the poem describes the speaker and his brother attempting to build a shelter. Then it returns to a consideration of Neanderthal anatomy, which suggests that it’s possible they did speak. We can’t know now, but perhaps soon we will: “When scientists / finish a life-size model of the esophagus, we’ll finally hear / what their voices must have sounded like.” This poem is thematically complex. It is skillfully crafted, like every other poem in the collection, which is a good thing because these writers have something to say.

Kai and Anders Carlson-Wee have mastered many of the strategies of poetic craft. For that reason, their work appeals to me as a poet. And the poems themselves are remarkably compassionate. For that reason, they appeal to me as a human being.