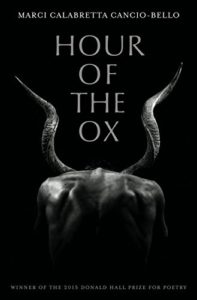

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello. Hour of the Ox. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. 62 pgs. $15.95.

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello. Hour of the Ox. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. 62 pgs. $15.95.

Hour of the Ox, which won the Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, tells a story of loss, of the richness of a former life and also the richness of a current life. Its author, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, succeeds in these poems through her reliance on imagery that is not only concrete but unusual, her trust in the power of metaphor, and her adoption of an authentic and informed yet thoughtfully quiet voice. Her language is evocative, restrained, and precise. The poems link personal memory with cultural tradition, such that disruption of one signifies disruption of the other.

“Your Mouth Is Full of Birds” is arranged into long-lined couplets. The form suggests control and order, appropriate for this poem which is trying so hard to contain its emotions, particularly of loss. Unlike in many couplets, most of the lines here are enjambed rather than end-stopped, a strategy that destabilizes the initial sense of control. Yet the lines in each couplet conclude with either true rhymes (follow / swallow), near rhymes (branches / branded), exact repetition (said / said), or, in one case, an evocative form of metonymy (birds / rookery). Cancio-Bello’s close attention to all elements of the line is matched by her subtle development of metaphor and her attractive word choice. Here is the poem:

You asked me once at dawn about forgiveness and I said

I didn’t think you had any need to be forgiven and you said

nothing, pointing instead to the tangerine branches

heavy with five-petaled flowers and a rookery of crows branded

like oiled umber in the sunlight. How grave the silences tucked

in each wing and beneath your tongue, silences you later tucked

into my suitcase when I wasn’t looking, letters written in memory

whose creases I smoothed over and over until I could remember

the gray trunks of the tangerine orchards, how each flower smelled,

each fruit peeled and quartered, full of tongues that still swell

in my dreams and burst into a hundred miles of telephone wires,

the silhouettes of birds still attached. Now, after all this while,

when you come to me at night with your mouth full of birds,

I think that you meant you forgave me for the rookery,

because they left their wings on my window, not yours. Oh how they follow

me still through this city, crying for you with every red-throated swallow.

Relationships between lines and sentences are particularly interesting in this poem. The first sentence requires four-and-a-half lines, and though it consists of multiple clauses, Cancio-Bello does not separate any of them with commas, letting them run into each other instead like a person speaking too quickly, without a pause to suggest grammar’s influence on meaning. She reserves the single comma to introduce the final series of phrases brimming with modifiers and objects but lacking any subject. I am examining this first sentence so closely because I am intrigued at how Cancio-Bello controls the pace of this poem and how the pace helps develop as well as subvert meaning. The enjambment between lines two and three is an example of such subversion, especially following the quickly spoken first two lines. Given the repetition of “and I said” and “and you said,” readers are expecting the words that follow “you said” to be a response to “I didn’t think you had any need to be forgiven.” But they’re not. The word that follows, “nothing,” is a word in the poem only, not a word the “you” utters. The imagery that follows is beautiful, but as the poem progresses, the speaker and the readers begin to realize that perhaps the speaker had misunderstood the “you” all along. Perhaps, when the “you” raised the subject of forgiveness, it wasn’t the “you” who required forgiveness but the speaker. The structure of this poem permits such ambiguity, which is almost always more interesting than certainty, without confusing the reader.

Finally, we reach the last couplet, which is also intriguingly ambiguous, the ambiguity heightened by the line break. Many poets would have broken the line after “me” rather than after “follow,” so that we’d have this final couplet: “because they left their wings on my window, not yours. Oh how they follow me / still through this city, crying for you with every red-throated swallow.” This slight shift doesn’t substantially affect the meaning of the first line, but it does dilute the possibilities of the second. Who is crying, “they” or “me”? “Red-throated” is a phrase often applied to birds, though not crows particularly, and “swallow” is of course also a common bird. In a less-accomplished poem, this language would serve only as a clever pun, but here the language encourages readers to recall the birds that have populated the entire poem as well as the title, “Your Mouth Is Full of Birds,” before they consider the alternate (and to my mind, more likely) possibility that the speaker is (also) “crying for you.”

The best poems reward such close reading, not merely for the purpose of literary analysis, but for instruction in craft. I am often astonished at the skill of contemporary poets. I read a poem, and I wonder, “How did she do that?” And then I think, “I want to do that, too.” Nearly all readers, I think, will enjoy the poems in Hour of the O, even when the poems themselves are somber. Readers who are also poets will want to read and reread, hovering above these pages in order to absorb just a little, and then a little more, of Cancio-Bello’s skill.