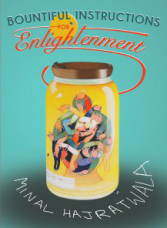

Minal Hajratwala. Bountiful Instructions for Enlightenment. The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, 2017. 120 pgs. $19.99.

One of the most interesting developments in the publication of contemporary poetry has been the turn to hybrid forms and hybrid collections. One factor is clearly related to technological developments that now permit text to be located on a page in unusual ways and also permit a mix of image and text that would have been difficult (and more crucially, expensive) just a generation ago. Another factor, I suspect, is the increasing diversity of cultures represented by publishers of contemporary poetry in English. Not every culture distinguishes among genres identically to mainstream British and American readers, nor does every culture assume that genres should not be mixed within a single published work. So we’re seeing collections of poetry especially that include pieces typeset as prose (whether we label them prose poems, flash, or something else), photographs and drawings, and short dramatic scripts. I suspect that one reason many of these collections that are challenging the boundaries of genre are published as poetry is because most poetry publishers are small, with limited staff and even less hierarchy, and much of this work is not sold in conventional bookstores. Such factors could discourage these publishers from experimentation, but the opposite seems to have occurred: these smaller publishers can do what they wish, and many of them are producing the most interesting work being published today.

Minal Hajratwala’s Bountiful Instructions for Enlightenment is one such collection. It contains poems that follow conventions in their appearance on the page, poems in columns of alternating voices, poems that look like prose, and finally a play. Despite these generic differences, the pieces are linked stylistically as well as thematically. Hajratwala juxtaposes classical with popular culture, putting characters from each in conversation with each other—Lady Gaga and Cassandra of Troy, for example. She also references individuals and characters from many different historic and geographic locations—Arjuna, Zitkala-Ŝa, the Buddha, Achilles, Margaret Mead. The poems are pleasurable to read because their content is often surprising, but they are not merely clever. Hajratwala encourages her readers to think not only about cultural distinctions and their sometimes arbitrary significance, but also about how members of a given culture perceive others. The book is playful and also thoughtful, challenging and wry, sometimes amusing and often very, very serious.

“Bodies of Water,” the third poem in the collection, plays on the multiple meanings of both nouns in the title. Describing Lake Victoria, it opens with what initially seem like a bizarre series of metaphors, though those metaphors soon make an appalling kind of sense:

Shape of brainstem, or ovary.

Northwest of the nipples of Kilamanjaro,

south of the Sudan,

the pale queen’s lake makes a gap in the continent

where, now, corpses rush—

a torrent of flesh so uniform you would not guess

they died for their differences

a hundred miles upstream.

One passes

every three minutes.

The initial metaphors, describing landscape in terms of reproduction and primitive thought, perhaps simply reaction more than thought, for it’s the “brainstem” not the brain that serves as the metaphor’s vehicle, prepare us for the subsequent event, the ethnic slaughter of Tutsis by Hutus in Rwanda. A few stanzas later, a European speaks:

I have never seen such cruelty to man,

claims the British ambassador, his tongue

distorting Hutu, Tutsi, Rwanda—

The ambassador’s statement is so ironic as to border on despair, for so many of the 20th and 21st centuries’ ethnic conflicts in Africa are the direct result of European colonialism. Many of the poem’s images rely on body parts, as does “tongue” above, as the speaker describes the bodies’ “dismemberment.” Then, she turns to her own response:

Two hand spans across the globe

I wonder whose hands will caress

the forty thousand, how will they shift

so many dripping dead to shallow graves &

in which language will they wail?

The poem critiques the British ambassador as well as the soldiers who have committed such atrocities. It also reminds the reader that we are all implicated, for one of the most disturbing facts is that there are so many events to compete with this atrocity, to debate the ambassador’s claim. This poem is perhaps the most serious in the collection, but many of the others explore history, revealing that history is the continuous story mistreatment of one group of humans by another.

“Bodies of Water” is a poem organized into conventional lines and stanzas, all the more horrifying because it so resembles a lyric on the page. The pieces in section three, “Archaeologies of the Present,” are more experimental. They adopt several of the conventions of social media and electronic search engines, each piece accompanied by a list of tags, and each tagged word appearing in bold face. “The Beautiful” has the following tags: “star, blood, cellular, closet, homo, hegemony,” and begins this way:

Luxury at this time in America means white robes with hoods, made of plush terrycloth, a material used in bathing towels in five-star hotels. The stars are a rating system indicating quality of accommodations, food, fame & so on.

To be a star one must be photogenic, emblematic, blank enough for projection: dreams, desires, even terrors. Homicides are enacted & reenacted for entertainment. Many means exist to simulate blood.

As soon as American readers see “white robes with hoods,” they are thinking KKK. The poem initially seems to suggest this is a misreading, but the second paragraph oddly confirms it. Members of the KKK have committed hundreds of homicides, to create terror among African Americans and others, and to offer entertainment for some white Americans. (Who can ever forget the photographs of mobs at lynchings?) “Luxury” is privilege, the ability to wear the terry-cloth robe or to wear or decline to wear the other robe with a hood. “The Beautiful” continues to enumerate daily rituals that signify luxury—varieties of cereal, lipstick, closet organizers, milk. The piece ends with a return to its beginning:

Homo fortified milk is sold in dozens of varieties to account for varying needs for fat, allergens, growth hormones, pesticides, etc.

All varieties, even chocolate, are white.

Bountiful Instructions for Enlightenment is worth reading and rereading for both its style and content. Its hybrid nature entices readers into close attention, heightening the effect of the content. We’ve never read about these events, our own cultures, or the cultures of others quite this way before. If the accomplishment of this collection is representative of The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective, I can’t wait to read more of their books.