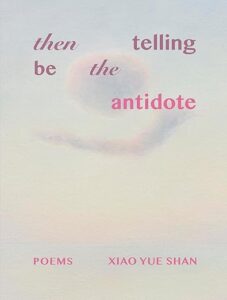

Xiao Yue Shan. then telling be the antidote. Tupelo Press, 2023. 79 pgs. $21.95.

Xiao Yue Shan. then telling be the antidote. Tupelo Press, 2023. 79 pgs. $21.95.

Xiao Yue Shan’s first full-length collection, then telling be the antidote, reveals the power of speech when speech and even to some extent thought are threatened. This doesn’t mean, however, that the poems are vociferous or strident, for they are not—they are meditative, soft-spoken, their tone often understated. Quiet as they are, they’re made of memorable language and imagery, sentences that are deceptively straightforward, their uncomplicated grammatical structures opening up multiple layers of meaning. Many of the poems are composed as one long stanza, often with long lines and left-justified margins, but several vary from this structure, exploring other options the page offers. They approach form, in other words, as thoughtfully as they consider word choice and metaphor. The collection is disciplined, filled with strong poems that each contribute to book’s effect.

“the coming of spring in the time of martial law” illustrates many of these characteristics. It begins:

I could tell you this: marigolds are a night flower.

in the hour of my birth there were men in the streets,

some with knives and some between skin and some

peeling open buds with swollen hands trying to find

a home to hide in. my mother fingered a ripened

bowl of hot water, carving out upon its surface the lines

by which our family would occur.

The opening statement is provocative; on the one hand, it’s puzzling—why such a set-up for an apparently insignificant fact? But then, readers might ask themselves, is it a fact? Are marigolds night flowers? Any gardener will tell you no. Marigolds thrive in sun. To say that the first line is wrong seems simplistic, though, so it might be more fruitful to ask how a marigold is a night flower. Already, the poem is flaunting mystery. The content of the second line seems entirely unrelated to the content of the first, as the tone becomes more ominous, with the first line’s adjective “night” contributing to this sense, through the next several lines that develop this sentence. Among all the things we don’t know by the end of the second sentence—why do the men have swollen hands? why would a home need to be a place to hide?—what we do know is that something here is not right. As Shan is developing the poem thematically in this opening section, she’s also developing a pattern of imagery she began with the marigolds. The men are “peeling open buds,” and her mother is fingering “a ripened / bowl.” Word by word, phrase by phrase, the writing is exceptionally careful.

Following the speaker’s birth, the poem continues with a litany of deaths: a teacher, a neighbor, someone whose offense was to complain about food, a mother and daughter. Here, everyone speaks in whispers, and readers mustn’t forget the title, “the coming of spring in the time of martial law,” its second half undercutting the symbolic resonance of its first half. Now, it’s night again, and “a song about marigolds prayed through the radio.” Now we get a sense of what the speaker meant by her opening line—marigolds are flowers that ease the dread of danger during anxious nights. The poem concludes with a description of the children’s attempts to reassure themselves: “stay still, / just like you’re dead. we whispered to hear ourselves speak.” The people are not silenced despite their government’s attempts to terrify. Their existence may in some ways be like death, but they remain alive, and the poem testifies to that life.

The poem immediately following the witness of “the coming of spring in the time of martial law” is “witness.” Although its language is more playful, the tone suggests that the poem is prompted by some unidentified sinister presence. Here it is in its entirety:

there is a long time and a time longed

for. a spectator and a combatant, the order

dreamless between them. river on pause, an especially dry

spring. departing day clearing the table of broken bread,

the light being something one turns off so as to finally sleep.

then there is someone to commit the act and someone who cries

enough. you will know once you have heard in the neverness

a promising silence. what does not happen here clasps

the entirety to its breast. what is everywhere cannot

happen here. anything short of forever is a long time,

there’s never any news coming from the other side,

save for some enormous music

we all cup our ears to hear.

This poem challenges readerly expectations several times. The pun on “long” in the first line could suggest that this will be a more light-hearted poem, or perhaps one marked by nostalgia. We could expect an additional pun in the following line, “spectator” and “spectacle” perhaps, and if not that, then the object a spectator would seek out. But what we get is “combatant.” Are the two companions, cooperating against some unnamed victim? Or is the combatant forced into this role for the pleasure of the spectator? By the poem’s mid-point, a victim emerges, “someone who cries / enough.” Time then seems to stretch toward eternity, not as reassurance but in hopelessness. Similar puzzling manipulations of language occur in the remaining lines, with “here” excluded from “everywhere” and “forever” apparently contrary to “a long time.” Time seems not to pass in this place, in the sense that nothing seems poised to change, aside from day turning to night, which is why the situation, whatever it is, seems so hopeless. However—human beings are creatures driven toward hope, and the poem offers subtle hints that all is not lost. There’s “a promising silence” and then music, “enormous music / we all cup our ears to hear.” This poem doesn’t offer readers a specific situation to analyze or categorize, instead implicitly suggesting that “here” could in fact be, if not “everywhere,” then anywhere, even in those places where we reassure ourselves that “it,” whatever it is, could never happen. Shan’s skill with the sonic effects of language and particularly with lineation is evident throughout the poem. Most telling is how the reader can ponder this poem without feeling confused, can sense its meaning without absolutely grasping it.

Some of the poems in then telling be the antidote are more concrete, offering the reader more stability, but they all leave us knowing that there’s much more to be understood from them, more certainly than a single reading, or three or four or five, can offer. The content of this book is often disturbing, but the poems’ meditative approach offers readers their own space of contemplation, apart from our frenetically anxious time. These are thoughtful poems capable of creating more thoughtful readers.