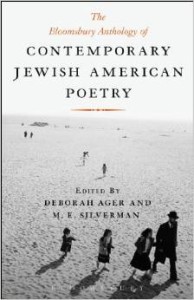

Deborah Ager and M.E. Silverman, eds. The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry. Bloomsbury, 2013. 329 pgs. $29.95

Deborah Ager and M.E. Silverman, eds. The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry. Bloomsbury, 2013. 329 pgs. $29.95

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

In their introduction to The Bloomsbury Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry, editors Deborah Ager and M.E. Silverman suggest that the parameters of inclusion in this anthology are broad. They implicitly define “contemporary” to include poets born after 1945, that is post World War II, an obviously defining moment in Jewish and Jewish American history. Although I can easily think of a few influential Jewish American poets whose ages make them ineligible for this collection, a cut-off date of 1945 nevertheless means that most living poets could be represented. Similarly, the editors define “Jewish” as an ethnic category that subsumes the religious category also known as “Jewish.” That is, religious observance isn’t a requirement for the poet, nor is a religious theme a requirement for the poems—although many of the poems do take Jewish ritual, belief, and practice as their topics.

The anthology includes the work of well over 100 poets, that number in itself testimony to its inclusive nature, most poets represented by 1-3 poems. Contributors range from household names (at least in poetic households)—David Lehman, Charles Bernstein, Liz Rosenberg, Edward Hirsch—through mid-career poets—Susan Rich, Arielle Greenberg, Ruth L. Schwartz—to poets who haven’t yet published their first collection—Sandra Cohen Margulius, Rachel Trousdale, Onna Solomon. Such an array of poets is among the anthology’s strengths, although it also of course makes the task of reviewing more difficult. Before I’d read even 100 pages, I felt overwhelmed, for I’d already paused over so many good poems, and I’d already noted at least a dozen titles by the contributors that I should check out. So I’ll just admit here that the poems I will discuss represent a tiny percentage of those I could discuss.

“Relax” by Ellen Bass is filled with humor and good advice. We needn’t worry about the future, the poem implies, because it’s bound to be filled with misfortune. Here are the opening lines:

Bad things are going to happen.

Your tomatoes will grow a fungus

and your cat will get run over.

Someone will leave the bag with the ice cream

melting in the car and throw

your blue cashmere sweater in the drier.

Your husband will sleep

with a girl your daughter’s age, her breasts spilling

out of her blouse. Or your wife

will remember she’s a lesbian

and leave you for the woman next door…

The juxtaposition of the elements in this list suggest that we grieve the significant and insignificant alike, that we cling to the mundane, that we will each likely experience some calamity we’d not even thought to be concerned about. This list is effective because the elements are both precise and universal. But all is not lost, even when all is lost. Here’s the last third of the poem:

There’s a Buddhist story of a woman chased by a tiger.

When she comes to a cliff, she sees a sturdy vine

and climbs half way down. But there’s also a tiger below.

And two mice—one white, one black—scurry out

and begin to gnaw at the vine. At this point

she notices a wild strawberry growing from a crevice.

She looks up, down, at the mice.

Then she eats the strawberry.

So here’s the view, the breeze, the pulse

in your throat. Your wallet will be stolen, you’ll get fat,

slip on the bathroom tiles of a foreign hotel

and crack your hip. You’ll be lonely.

Oh taste how sweet and tart

the red juice is, how the tiny seeds

crunch between your teeth.

The taste and scent and texture of a single strawberry makes all of the other disasters worth it. The poem develops through the accumulation of detail, and seems to be primarily a clever list that will easily persuade us to continue reading—though perhaps not bear up to rereading if it remains simply a clever list. The Buddhist story seems initially to comment on the speaker’s worries—life may be bad, but it could always get worse. But the poem turns here, not toward further tragedy but toward pleasure. And the turn leads to the most overt Jewish reference in the poem: “Oh taste.” “And see,” we might want to say, “how good the Lord is,” completing the line from psalm 34. The allusion is more oblique than many, but the imagery enacts the lesson from the psalm, three lines developing an image that appeals to nearly every human sense, as if (think of it!) sensual pleasure is what we are made for.

“The Children’s Memorial at Yad Vashern” by Philip Schultz is much more serious, its solemn tone a response to its solemn subject. Observing a group of photographs, the speaker imagines what knowledge these children have acquired: “They understand they are no longer children, / that death is redundant, and mundane.” The speaker questions God, and the children question God, that divine being who this time does not intervene in history. The poem concludes with lines that straddle resignation and acceptance:

We look at their faces and their faces look at us.

They know we are pious.

They know we grieve.

But they also know we will soon leave.

We are not their mothers and fathers,

who also could not save them.

The line breaks here follow the structure of the sentences, and the sentence structure is equally straightforward, each one beginning subject-verb. The tone—objective, neutral—permits the horror of the event to be made manifest.

The editors of this anthology have done an extraordinarily good job in representing the diversity of American Jewish poetry. It is diverse not only in the ways they state in their introduction, but it’s also stylistically diverse, so it avoids the monotony of some anthologies wherein the poets are too aesthetically similar. Yet regardless of style, the poems are consistently energetic and engaging. It’s a collection I want to return to, though I hesitate, because it’s also a collection that encourages me to seek out further work by so many of these contributors.

Pingback: Review of The Floating Door by M.E. Silverman | Lynn Domina, Poet