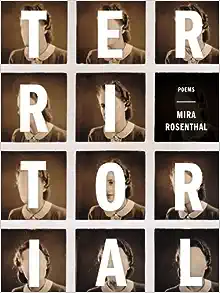

Mira Rosenthal. Territorial. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022. 93 pages. $18.00.

Mira Rosenthal. Territorial. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022. 93 pages. $18.00.

Mira Rosenthal’s poetry is both stark and lyrical—stark in its themes and often forms, for the poems often exploit the white space surrounding the lines, yet also very musical, the sounds of her words repeating and revising each other. The reader can’t help but pay attention. The poems in her second collection, Territorial, (Rosenthal is also a translator of contemporary Polish poetry and has published several collections of her translations) consider the land and geography, especially the violence committed against it and its creatures. They also consider the territory of the human body, particularly the violence and threats of violence against female bodies. Most importantly, they implicitly and explicitly link environmental violence with gendered violence.

“Squirrels of North America” initially seems simply to observe that most common of rodents:

From grab to flit, from clutch to twist, through leaf

twitch to the wind’s acoustic shifts, in parks, in yards,

one splayed in the shade below a picnic table, belly

down, arms out like a kite trying to fly from summer

heat & ash that blackened the nostrils of every breathing

thing in the vicinity of a swamp in flame…

In this opening, I first notice the repeated “i” sounds: “flit,” “twist,” “twitch, “wind’s,” “shifts.” Then I notice how many of the “i” sounds are followed with a “t.” Then I notice the repeated “l” sounds, in “flit” but then also in “clutch” (which also has the “tch” of some of the other words) and “leaf.” Then in the second couplet, Rosenthal emphasizes the “a” while maintaining the consonance of the “l.” Similar sounds occur in the third couplet. A high proportion of the words are also monosyllabic, permitting a correspondingly high proportion of stressed syllables. So many sonic elements are working together here—I’m caught up in the music and nearly forget that the lines are describing the action of squirrels. If all this poem did was continue this musically energetic description, it would be fun and memorable and almost certainly successful.

But it does so much more. Mid-way through the poem, the speaker introduces herself: “I disappeared / down one of those paths with a nice enough guy…” She’s a teenager, trusting nature, life, and the boy she’s with: “I trusted being this far in with no other // ear to hear me.” But then the boy says, “You know, you should be / more careful.” Suddenly, her experience becomes sinister. I wonder at the boy’s motive, which seems to be both to frighten her and to position himself as heroic because he doesn’t assault her, but he can only acquire this creepy virtue by frightening her, by suggesting what he could do if he wanted. For the speaker, everything changes:

…his words spread like a blanket over my young

face to shield the stunned animal & a knot of hard

acorn lodged in my throat & I swallowed & swallowed it

down. I was safe, but only for now. The boy took

my hand, later, by the fire & fastened his fingers to mine…

When we look back at the beginning of the poem, we notice that much of the vocabulary implies danger: “grab,” “clutch,” “twist.” The squirrels are acrobatic, but the language also unifies the poem well before the reader recognizes the true subject. In the two couplets that remain, Rosenthal returns to imagery evocative of squirrels, but the tone has irrevocably chilled:

…I kept silent, eyes fixed on the coals as tiny claws

gripped bark just beyond the frame of light, from grasp

to hide, from lash to flight, something wild gone dark.

Rosenthal maintains her attention to sound and rhythm, even relying again on “l” and “a,” but there’s nothing playful left. The speaker and the readers understand that she’ll never be safe again, that she, indeed, never was safe at all.

An equally haunting poem is “The Apron,” also composed in couplets. It begins with a description of an ordinary apron and a person searching through stacks of ordinary saved objects. Its obsessiveness soon emerges, and the poem becomes self-reflexive, the speaker calling our attention to her associative connections between objects and events with the phrase “Which reminds me.” In writing the poem, the speaker is longing to rewrite history. Early on, the apron string reminds the speaker of “the plank of an arm, fallen // from a body asleep in a chair…” Here, the image seems to be just a metaphor, the arm and the body serving the description of the apron. Later, this body becomes a “her” the speaker recalls and imagines, a woman who performs ordinary tasks, needlework, baking, protecting her dress with the apron. Then the speaker admits, “I reason I just might save her / this time, in the dank garage, saying please // don’t pull the trigger.” The line breaks here are masterful, the delay between “save her” and “this time” emphasizing how the speaker has likely tried again and again to change the course of events. Through an additional series of associative metaphors, the poem reaches its conclusion:

…she pressed the phone there, calling my father

& how he drove over & how he found her

slumped in the chair, her arm fallen open,

head bowed to her lap, as if reading.

The earlier “body asleep in a chair” suddenly isn’t just a body and isn’t merely asleep. This poem seems to follow a mind thinking, but Rosenthal’s selection and placement of detail reveals what a careful and thoughtful writer she is.

Several of the poems in this collection are more stylistically experimental—“The Invention of an Interstate System” and “In the Background of Silence” are two compelling examples that rely on long lines, with each line separated from the others into its own stanza. In the poems formatted this way, Rosenthal’s associative leaps are more extreme, requiring the reader to be even more attentive, but the poems invariably reward the reader’s effort.

Nothing in these poems is wasted, not a single word or syllable or sound. In poem after poem throughout Territorial, the writing is tight and musical and concrete, and the substance is profound.