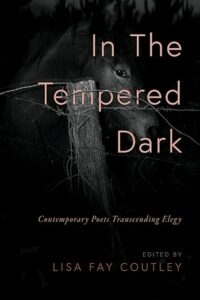

Lisa Fay Coutley, ed. In the Tempered Dark: Contemporary Poets Transcending Elegy. Black Lawrence Press, 2023. 403 pgs. $29.95.

Lisa Fay Coutley, ed. In the Tempered Dark: Contemporary Poets Transcending Elegy. Black Lawrence Press, 2023. 403 pgs. $29.95.

Lisa Fay Coutley has done a masterful job editing this new ambitious anthology of poems responding to grief. As every reader knows, grief is always complicated—because our feelings about the deceased are often complicated and because every death, as Hopkins so eloquently articulates, reminds us of our own mortality. The poems in In the Tempered Dark acknowledge the range of responses individuals experience, for let’s face it, not everyone who dies is a “loved one,” and even loved ones aren’t always loved absolutely or absolutely all the time.

And sometimes people or things are gone without being dead. Grief is accompanied by frustration, relief, guilt, despair, anger, bewilderment. So the poems here are more honest than many eulogies, but the anthology succeeds not only because of its variety of content. Stylistically, the poems are also diverse, which makes turning the page refreshing and often surprising. The range of voices confirms that this is an anthology, not simply a group of poems that could have been written by the same person. In addition, in a unique feature, each contributor has written a prose accompaniment to their poems, providing context for the content or thoughts on composition.

Contributors include poets who are far along in their careers and already well known—Diane Seuss, Janet Burroway, Ilya Kaminsky—younger poets who have published one or two or three collections—W. Todd Kaneko, Malachi Black, Meg Day—as well as poets who will be new to many readers. This makes it challenging to cite just a few, but it also means that readers of the book will be richly rewarded regardless of how many reviews they’ve read. Rather than focus on one or two representative poems to examine in detail, as I generally do with single-author collections, I’ll comment briefly on several.

Composed on couplets, Rebecca Aranson’s “Star Dust” initially looks spare, with its regularity and frequent space breaks between stanzas. It seems to begin in media res: “And then somehow a slipping away, as if wanting no one to linger with you / at the door making plans for next time. You had come without a coat…” Readers quickly understand the circumstances. The deceased was likely elderly, the speaker’s father, living in a nursing home where the speaker’s mother also resides. The death seems to have been one many of us hope for, “a slipping away” after a long life. This knowledge, however, does not mitigate the grief of the survivors, nor does it do much to soften our knowledge of our human condition. In its last section, the poem brings the reader into its circumstances by extending outward. Here are its final lines:

Grief is in you from the start and in you at the end

and though sometimes your days are flooded with it,

and sometimes your days are clear, we are made of it

as much as we are made of the ruins

of the first flaming star, whose far flung dust still spins

us into being.

Aronson here complicates that uplifting cliché, that we are made of stardust, revealing a deeper and more complete truth.

Victoria Chang’s prose poem “The Clock” also explores the speaker’s father’s situation. Though alive, he’s experiencing dementia, an inability to think abstractly that Chang initially explores through the symbolism of an analog clock face. Interpreting it is more complicated than we often realize, with the numbers each standing for more than one idea—seconds, minutes, hours. About two-thirds of the way through the poem, she introduces another metaphor, leading to her conclusion:

If you unfold an origami swan, and flatten the paper, is the paper sad because it has seen the shape of the swan or does it aspire towards flatness, a life without creases? My father is the paper. He remembers the swan but can’t name it. He no longer knows the paper swan represents an animal swan. His brain is the water the animal swan once swam in, holds everything, but when thawed, all the fish disappear. Most of the words we say have something to do with fish. And when they’re gone, they’re gone.

What does it mean to remember without access to words? Each of the metaphors in this poem reveals something about the nature of human thought, our ability to understand one thing as another, to see a piece of paper and recall an animal, even an animal we might never have seen, to see a numeral and know that it signifies both a word and a concept. For readers and writers, this knowledge that words disappear can be particularly disturbing, even as we savor the image of a folded piece of paper and its representation of an elegant creature.

Several poems in this anthology grieve the non-human, including Jenny Dasre-Orafai’s “We Lost Three Billion Birds in Forty-Nine Years.” The speaker attempts to visualize the three billion, a number that is, if not literally uncountable, nevertheless unimaginable. The poem explores some of the other absences that follow, as well as the possibilities the birds’ absence ironically provide. The concluding lines are particularly suggestive: “We’ve got so much food in the feeder and / the other animals can’t get their fill.” The other animals—perhaps squirrels or chipmunks or skunks, perhaps ourselves. These lines articulate a call to conscience for human beings whose insatiable appetites have created this crisis of climate change and extinction.

Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s “They were armed with long guns” is one of the most stylistically unusual poems as well as one of the most overtly political in the anthology. It is arranged into ten sections, beginning with a single-line opening: “and that’s how everyone they shot, died.” We know immediately that this poem will address gun violence in America. Three of the sections are titled “I, Rearrangement Servant” and consist of words composed of letters contained in the title, for example “Where were you last night? / Sheltering // in the theater…” and “it is early to be dying.” Three of the sections begin with the line, “I fear for my life at the following places (circle all that apply)” and contain options like “Shopping Malls,” “Parties,” and “Landmarks.” The third of these sections, however, contains only one word repeated twelve times: “School.” Two of the sections are more conventionally poetic in their appearance. In one, the speaker is leading a class discussion on a poem describing murder. In the final section, the speaker describes a “dollbaby” belonging to a friend’s son, a doll named Pete that shoots bullets out of its hand and feet. This toy that should provide comfort instead introduces the child to that most American characteristic: a gun. “They were armed with long guns” is conceptually ambitious and memorable in its execution.

All of the poems in this book merit extended discussion. Lisa Fay Coutley has thoughtfully edited In the Tempered Dark, selecting poems that complement each other in form as well as content, and choosing poems that also succeed individually in terms of craft. The range of the poems taken as a whole and the accomplishment of each one create a gratifying reading experience.