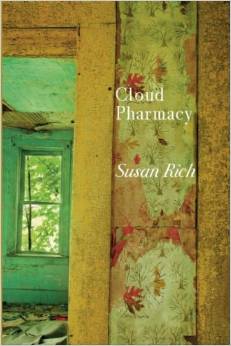

Susan Rich. Cloud Pharmacy. White Pine Press (print); Two Silvias Press (ebook), 2014. 67 pgs. $16.00

Susan Rich. Cloud Pharmacy. White Pine Press (print); Two Silvias Press (ebook), 2014. 67 pgs. $16.00

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

I have read Susan Rich’s Cloud Pharmacy several times now, intrigued by its motifs, its figurative language, the speaker’s precision and simultaneous detachment. The poems are kaleidoscopic. Images coalesce and break apart; my attention follows one pattern and then notices another and then another. Each reading reveals a new entry point into the relationships among individual lines and poems and the collection as a whole. The poems are frequently characterized by an ekphrastic impulse, even when they are not responding directly to another piece of art. For the most part, Rich prefers the shorter line, shorter stanza, and often, the comparatively short poem. Composed primarily as lyrics, the poems nevertheless avoid the simple scenic mode or a straightforward autobiographical rendering of experience. The reader is invited in through stimulating language, words that create interesting sonic effects as well as phrases that develop compelling visual impressions.

I’ll discuss two of the poems in this review, The first, “American History,” is a commentary on the effects of our contemporary political culture, though the political commentary is muted, and it initially seems like a nostalgic look at all that has changed since the speaker’s childhood. Here are the opening lines:

Someday soon I’ll be saying, at school

there were chalkboards, at school

we read books made of paper,

we drank milk from small cartons…

So far, the changes, much as some of us might bemoan them, are comparatively neutral. Technologies of reading have changed, but those changes involve no moral component. But then the speaker recalls other details, and the changes recalled by the middle of the poem are more disturbing: “At school we met children unlike us, / studied evolution, enjoyed recess, plenty of food.” Despite efforts toward diversity, the student body in many schools remains homogeneous. And the content of virtually every academic discipline has become controversial, with the study (or not) of evolution evoking perhaps the most vociferous debate. The poem continues with a gesture toward Gwendolyn Brooks—“At school we sang harmonies of Lennon- / McCartney, we were cool;” but then turns toward a comparatively direct statement of its theme: “all paid for by taxpayers // supporting an ordinary American school.” The poem concludes with this critique of contemporary divisions in American culture, divisions so deep that an “ordinary American school” has become endangered. As with all successful poems, the success of “American History” stems from its approach to its subject, not from the subject itself. The poem brims with concrete detail, each likely recalling the reader’s own school days. Until the last two lines, the tone shifts between neutral and nostalgic; at the conclusion, the tone becomes more challenging but remains understated. The poet, that is, trusts her material and her readers, and she respects her craft.

I am most intrigued by the poems in section three of the collection, “Dark Room.” They consider the work of photographer Hannah Maynard who, according to Rich’s notes, experimented with self-portraits involving multiple exposures of her film following the death of her daughter, Lillie. Maynard’s idea is interesting, and so are the poems that respond to the photographs. As with the best of ekphrastic poetry, these poems are stimulated by the photographs, but they do much more than simply describe—a particular challenge when the reader is unlikely to be familiar with the original piece of art. And like the best of poems in a series, each one stands fully on its own but also gathers significance from the poems surrounding it. “The Process of Unraveling in Plain Sight” presents Hannah in the third person; she stares out into the world, appearing to gaze at viewers, including the speaker of the poem. Early in the poem, Rich conveys the effect of the multiple exposures:

Then she overlaps the images and leaves

no line of separation

but splits herself open like a magic trick;

now she’s Hannah times three.

Here, the break after the first quoted line appears to suggest that Hannah removes herself from the space, though the next line reveals that her multiple images become amorphous, indistinct from one another. She isn’t absent after all, but hyper-present. Yet, paradoxically, she isn’t present as an individual but as an amplification, one image juxtaposed against or superimposed upon another. Also paradoxically, the line in which she leaves “no line of separation” itself separates one description of the portrait from the next. Two lines later, the speaker describes the image this way: “a severed body (hung // in a golden frame, floating on tired air). The stanza break after “hung” emphasizes the image of the hanging body, which we discover is only hanging in a frame—but we cannot forget the gruesome image of “a severed body (hung.” The poem ends with the assertion that Hannah “Does not, // does not, does not allow / Lillie to stay dead.” I will remember the imagery in this poem because it is vivid but also because it works on two levels, as a description of a more literal photographic image and also as poetic imagery.

Cloud Pharmacy is a book to be read intently rather than merely skimmed. It is Susan Rich’s fourth collection of poetry, and for that I am grateful—not simply because there’s a sufficient body of her work out in the world now, but because her rate of publication (four books in fourteen years) suggests that she is a working poet who is likely to write and publish more.