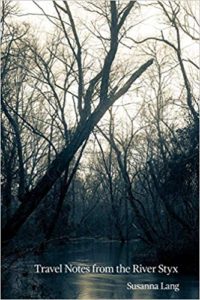

Susanna Lang. Travel Notes from the River Styx. Terrapin Books, 2017. 92 pgs. $16.00.

Susanna Lang. Travel Notes from the River Styx. Terrapin Books, 2017. 92 pgs. $16.00.

I’d had Susanna Lang’s Travel Notes from the River Styx in my to-be-read pile for some time, and when I finally picked it up recently, reading it in one sitting, my first thought was that I wished I’d read it sooner. It’s just fantastic. You should all read it. I’d end this review right here, but I know you, dear reader, have heard such claims over and over again, and you’re skeptical. So let me try to convince you.

This collection is a meditation on time and distance, separation and return. Many departures, as the title suggests, are physically permanent, though memory can keep people close or permit them to arise without previous notice into the present. Memory itself sometimes departs too, frustratingly, sadly, though a person remains near. Travel Notes from the River Styx explores relationships and ancestry, particularly the details of ancestry created by war, displacement, and refugee status.

The most prominent figure in this book is the speaker’s father. In the opening poem, “Road Trip,” the speaker travels through mountains, along a road she’s traveled before, and experiences a mystical visit, perhaps through a dream, from her father, mother, and grandmother. The visitors transcend the boundary between life and death, of course, but transcend time in other ways also, more comfortable here than they had sometimes been in life. Written primarily in tercets, the poem opens with a contrast between familiarity and difference:

You remember the signs along the road

for underground caves, stalactites,

zip lines, miracles. There was a sign

I hadn’t noticed before—Cavern, Ice Age Bones.

As if, on the way south, we could take a detour,

pass through an earlier time, visit our ancestors

as we visited grandparents when we were children,

our fathers driving for days punctuated by exits

advertising cheap motels where we didn’t stop to sleep.

What the speaker hadn’t noticed before is an invitation to deeper time, a kind of visit that would be miraculous, though probably unlike the miracles advertised in the first stanza. Lang’s preference for regular stanzas—couplets, tercets, quatrains—is evident throughout the collection. Here, the regularity suggests a sort of control that helps manage the unpredictability of a mystical experience and the overwhelming power grief can exert. The regularity along with the comparatively long lines also affects the pace, slowing it down to ensure a more contemplative reception of the story the speaker will tell. A few stanzas later, Lang describes the visit with her more recent ancestors:

…the rain fell as it always falls on these roads.

It’s a story you and I tell about these trips,

the fearful crossing through the mountains, in rain

or snow or fog. This time my father waited

where I stopped for the night, my mother busy

in the kitchen though she, too, was a visitor in that place.

She moved back and forth from counter to stove

with her mother, who was at home there, the rooms

dark in the early evening as if underground.

They set my place at the table, though as in the old stories,

I cannot tell you what we ate. The rules have not changed

about what you can and cannot bring back.

My father was still in his nightshirt but he stood unaided

as he had not done in years, a glass in his hand,

proposing a toast. Has it been like this for you,

have you found the house where your dead linger

along some other road, in the course of some other trip?

The direct question that concludes this section, asked of the “you” who has been addressed throughout the poem but also, of course, of the reader, is particularly effective. The details indicate that the speaker’s experience consists of a moment within the legend of continuous human experience: “as in the old stories, / I cannot tell you what we ate.” She shifts between these events that occur within a type of universal time and her own specific role, describing a man recognizably her father but not her father as he was at the end of his life. And then with the question she turns outward, linking her story to the suggestion of others. Her word choice here, “linger,” “some other road,” “some other trip” reinforces her theme, how time allows multiple moments to occur simultaneously.

The poem concludes by linking all of these ideas imagistically:

…Chanterelles rise

from below, ruffled like vivid cloth; rise from those caverns

where the signs call us to witness ice age bones,

where those we’ve loved wait for us to stop on our way

and share a meal, even if we cannot tell later

what wine sparkles in the glass we raise.

These last lines are particularly satisfying. They return us to the opening of the poem, and to the line I quoted above with the speaker’s father “proposing a toast.” Though the poem certainly explores grief, the last line celebrates the speaker’s experiences, even as some of them have been of loss. Yes, the dead wait somewhere; nevertheless, “wine sparkles in the glass we raise.”

In its tone, craft, and subject, “Road Trip” is representative of many of the poems in the collection. “Welcome” is somewhat different, though it, too, feels contemplative. Again, the poem is addressed to an indeterminate “you. Although the speaker refers to herself initially in the first person singular, she assumes a collective responsibility, speaking for a community that includes other living creatures as well as inanimate elements of nature. Here is the poem:

Now that you are here, I want you to know

the difficulty of water.

How the river is so low, we dream of floating.

How we try the pump though the well has run dry—

it’s a form of prayer.

I want you to know the despair of sea turtles

and the homesickness of mackerel.

How the evening is nostalgic for the voices

of sparrows, how the wind

when it rises brings only dust from the road.

I realize that you do not have enough buckets to fill our wells,

that you do not make rain.

Still, you should know. For one day at least,

you should taste our thirst.

Lang’s skill with craft is evident throughout this poem, especially in her use of assonance and internal rhyme and her decisions regarding line breaks. Most memorable, however, is the voice. It’s authentic and trustworthy, partly because it is so quiet. In this poem, the matter-of-fact tone paradoxically reinforces the speaker’s desperation. In every poem in the collection, the voice is reassuring yet honest, inviting the reader into an examined life.