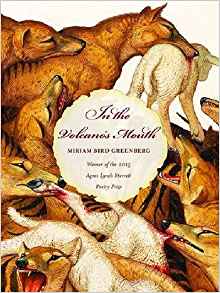

Miriam Bird Greenberg. In the Volcano’s Mouth. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. 101 pgs. $15.95.

Miriam Bird Greenberg. In the Volcano’s Mouth. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. 101 pgs. $15.95.

The poems in Miriam Bird Greenberg’s first full-length collection, In the Volcano’s Mouth, are compelling for both their content and craft, but be warned—the collection is not an easy read. There’s very little safety here, and what safety there is is temporary. The book explores implicit violence, threat, unease, with the reader becoming increasingly apprehensive.

An early poem, “Valediction,” explores the speaker’s childhood memory, of a mother, yes, but also of a much more sinister image. Referencing Octavio Paz, the poem begins,

My earliest memory

is aboard a train, drowsing. My mother

covers my eyes

suddenly with her hand, startling

me awake. Light spills

between her fingers, then a long shadow,

hanging from a pole.

Flag of civil

wars, swaying

on its rope…

The poem begins comfortably, even nostalgically. But the nostalgia is a decoy, for although the mother does act protectively, the image that follows, “a long shadow, / handing from a pole” is horrifying. Greenberg’s attention to the line in this excerpt enhances the effects of the sentences. The second line, for example, reinforces the deceptive hint of nostalgia as “My mother” is positioned adjacently to the suggestive “drowsing.” Then the break between lines three and four, with “suddenly” introducing line four, contributes to the abrupt shift. Despite the mother’s attempt to shield her child, the speaker nevertheless glimpses the “long shadow.” The next line, “hanging from a pole,” one of the few in the poems where a line consists of a single complete grammatical unit, is as disturbing as it is in part because the stark phrase is isolated from other material. Greenberg’s next line—and stanza—break emphasizes the particular disruption of civil wars, when danger arises not from beyond borders but from within them.

The poem progresses through linked images until we reach the last couple sentences and stanzas. Soldiers, we are told

lie

asleep as animals

bedded down

at their tethers. One covers

the back of his neck

with his hand, as if warding off a blow

in his sleep.

These concluding sentences recall the opening, when the speaker was nearly asleep and then startled awake in time to perceive the residue of violence. These lines suggest that the world contains no safe space, as even in sleep a man must settle into a posture of defense.

I admire how this poem proceeds, the experience conveyed subtly yet directly. Its format requires deliberate reading, which permits the content to unfold gently—if gentleness is not too paradoxical for the revelations that ensue.

Throughout In the Volcano’s Mouth, the poems are most often composed in short stanzas, particularly couplets, with some lines indented as in “Valediction” above. “How Loss Inhabits a Body” consists of twenty-three couplets followed by a final single line, with alternating lines indented. Its strategy, however, is quite different from “Valediction,” as it opens with a series of imaginative similes responding to the title:

Like your collar is always turned up.

Like the wind twisting in your ears, conch

and cilia. Like the spine of the roof

peering behind other roof-spines, green

with moss. Like waking up as someone

else. Like when you’re having sex, but you’re not

quite you; you’re a German woman

who can strip and clean an automatic weapon,

and reassemble it in the time it takes to fry an egg.

This poem opens suggestively enough, with loss compared to a chill. References to the body lead to a metaphor in which a body part becomes the vehicle rather than the tenor, “spine of the roof.” The most startling metaphor occurs a few lines later, “a German woman / who can strip and clean” not a bed but “an automatic weapon, / and reassemble it in the time it takes to fry an egg.” Here, Greenberg incorporates a more traditional domestic image, “fry an egg,” to emphasize the most undomestic of skills, “strip and clean an automatic weapon.” Juxtapositions like this typify Greenberg’s work. They keep the reader nearly constantly off balance, guarded against what might come next, just as the speaker and other characters are.

The poems in In the Volcano’s Mouth are not apocalyptic, but they are ominous. They are set not in the peaceable kingdom but in the bloody and carnivorous world we actually inhabit. This collection won the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press, an award it clearly deserves. Greenberg’s voice is already distinctive, and each of these poems calls out for multiple readings.