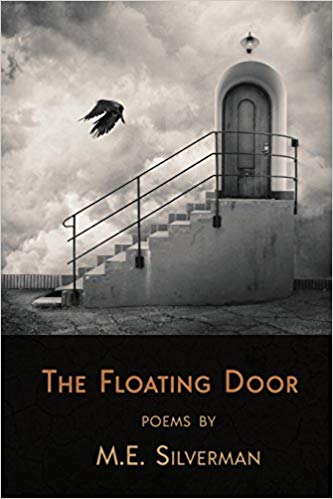

The Floating Door. M.E. Silverman. Glass Lyre Press, 2018. 83 pgs. $16.00.

M.E. Silverman’s The Floating Door features a few series of overtly related poems interspersed with other individual poems that complement them thematically. One series consists of poems in “Response to” contemporary concerns, from the mundane and mildly amusing, e.g. “Step on a Crack,” to the more disturbing yet still somehow amusing, e.g. “I Can’t Get off the Couch.” Another series features “Mud Man” and “Mud Angel.” Yet another explores the life of “The Last Jew” in Afghanistan—many of my favorite poems in the collection occur within this series. The collection includes several prose poems, as well as traditionally lineated poems, most often written in free verse, demonstrating Silverman’s attention to craft.

The book is interesting for its craft but even more interesting for its thematic strategies, juxtaposing explorations of spirituality and religious practice with descriptions of the ordinary encounters of 21st century life, challenging temptations to separate the transcendent from the imminent, the sublime from the dismal.

“The Last Jew Celebrates the New Year with His Dead Friend, Ishaq Levin” begins by setting the stage, the last Jew tired of being last:

After seven years,

he digs him up

for the High Holy Holidays,

brings him home

to the space they once shared,

slaps him down

in a borrowed rocker

in the empty café.

The act, of course, is absurd, though perhaps no more absurd—though clearly not implausible—than the fact that any given country would be home to its “last Jew.” The two celebrate the holy day together, though “celebrate” might exaggerate their activity:

The sun snaps shut

like a casket lid over Flower Street.

By the open door,

a table is set for two.

Levin remains silent,

still holds a grudge,

jealous that Zablon outlived him

but more concerned with his hands

tied to the chair

with the tzitzit from his old tallit.

He sits wide-eyed, surprised,

slightly displeased,

even more thin skinned

than before, …

I’ve often observed that as people age, barring a stroke or other serious brain injury, they just become more like they always were; for Levin, this development seems to follow him even into death. Zablon isn’t lonely simply for company, nor is he missing a specific person—he’s lonely for the companionship of someone who understands his worldview, his ethnic and religious commitments, so lonely that digging up a grumpy corpse improves his evening.

The act acquires symbolic value of course, the entire poem functioning as a metaphor for the power of the dead among the living, even moreso when cultural memory is infused with genocide, but it succeeds primarily because of its literal meaning. Silverman creates two interesting characters, men who might not seem to have a lot in common with the reader, but men who resemble us nevertheless. For who among us hasn’t experienced this deep longing, and who among us hasn’t also rested in the comfort of our character flaws? These men are interesting because of their oddities, though those oddities aren’t really so odd.

“Mud Angel” is tonally quite different from “The Last Jew Celebrates the New Year with His Dead Friend, Ishaq Levin.” It is written in short couplets, with a comparatively equal distribution of enjambed and end-stopped lines. Here is the poem:

In the barn, he removes

& folds his clipped wings,

a blue-gray, not from dye

but from age, grime, storage.

Gently, the bruised feathers

brush the scar on his left cheek.

At night, in flight,

it itches more

like a healing wound

open to air. Every morning,

every morning he looks down

from the loft, rests

a hand on a bale of hay,

thinks about chores

& closes the trunk, thick

with dust & dirt,

then turns, his back bare

with phantom limbs.

The imagery in this poem—“bruised feathers,” “itches more / like a healing wound”—is memorable and assists the reader in imaginatively embodying this figure. For what is a mud angel, really, but a human being, made of clay as Genesis tells us and “little less than angels” as Psalms says. The sonic devices are equally effective, especially the alliteration and consonance: “bruised feathers / brush,” “closes the trunk, thick / with dust & dirt, / then turns, his back bare.” Silverman’s reliance on monosyllabic words emphasizes these hard sounds and permits these short lines to be comprised of predominantly stressed syllables. That is, although the poem isn’t metrically regular, it often nearly sounds so and occasionally becomes so: “At night, in flight, / it itches more…” In this poem particularly, Silverman exploits many of the poetic devices available to him without becoming shackled by them.

The collection also contains several prose poems, many of which emphasize narrative and in another context might be called flash. These pieces are often highly imaginative, bordering on magical realism. “Hurricane Dreams,” for example, opens with the speaker’s father pulling “a hairless cat out of my chest,” the father immediately becoming linked to Abraham. The poem questions the father’s power; he is not God and therefore “cannot breathe life into something so small as me,” yet as we all know can deliver death. Any piece of literature that analogizes a father and son as Abraham and Isaac is bound to become ominous, as this one does. Although it concludes with the collection’s mystical title image, the last sentence remains more ambiguous than the story from Genesis is, disturbing as that story nevertheless is: “I breathe & breathe & obey for the love of God, the way Isaac did with his eyes closed, without murmuring, aware of the sharp steel but not what his father hears, what his father knows, yet still willing to go through the floating door.” In the canonical story, what the father hears is God’s revision of his command to kill Isaac, but what the father also knows is his willingness to have committed that act. The poem seems to conclude with meditative trust, but the speaker’s willingness to submit himself to the father doesn’t relieve the poem of its sinister undercurrent. The reader can’t help but respond ambivalently, and evoking that ambivalence is perhaps Silverman’s best decision here, for the poem becomes much more memorable than if it had resolutely (and likely falsely) resolved this dilemma.

M.E. Silverman’s work has been widely published in literary journals, and he is as active as an editor as he is as a writer. I was, in fact, introduced to his work through an anthology he edited, Bloomsbury’s Anthology of Contemporary Jewish American Poetry, which I also reviewed here. I appreciate his vision in both roles, and I’m looking forward to whatever he publishes next.