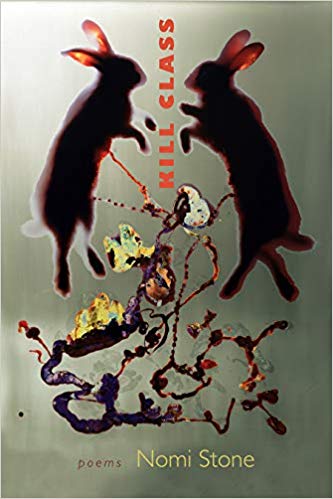

Nomi Stone. Kill Class. Tupelo Press, 2019. 90 pgs. $17.95.

Occasionally a poet emerges whose personal experience or knowledge permits readers entrance into worlds they might never otherwise know. These poets write books that change our thinking about our lives and about how literature can intervene in the actual, material world. Think about Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam (which I reviewed here) or Tyehimba Jess’ Olio or Fatimah Asghar’s If They Come for Us. Nomi Stone is one such poet, and Kill Class, her second collection of poetry, is one such book. Stone is formally trained as an anthropologist as well as an accomplished poet; Kill Class could not have been written otherwise. In these poems, the speaker is embedded on a military training base, observing

observing and participating in “games” intended to teach soldiers how to make war.

Though written primarily in free verse, the poems assume many forms, taking advantage of the options for line lengths and line breaks that free verse allows, and they range from very short (3 lines) to unusually long (6 pages). Stone is skilled enough with craft, that is, to exploit the characteristics of language in order to explore her subject fully. By exploring such a disturbing topic through a variety of forms, the poems continually surprise, startle, and horrify.

The title poem is the longest in the collection. Details emphasize the game-like nature of the soldiers’ training. “The story says we are in the country of Pineland,” the poem begins, eventually describing the speaker’s role:

The story says I join the guerillas.

The story says I carry this tent in.

Three cages at the wood-line:

the goat, the chickens,

a solitary white rabbit.

That rabbit, seemingly introduced here as simply a bit of local color, will become crucially significant, revealing the speaker’s character as one who refuses the false restriction of an either / or possibility, and therefore as one unsuitable for “Kill Class.” But first, she reveals more about her role:

Commander: You are Gypsy, from Taylor-town, the widow of Joker,

one of the fallen guerillas.

They make me a fighter.

One woman among 40 guerillas

and the 12 American soldiers

secretly training them to overthrow

their country’s government.

Joker fell heroically, and our child—there was a child—they made

me eat his ashes.

The syntax here is puzzling—does the second “they” have the same antecedent as the first “they”? Although it would seem so grammatically, logically it would seem not; surely those forcing her to eat her own child’s ashes must be the enemies. People identified as “we” or “us” could never behave so barbarically. Except. Except. This is a class that teaches participants how to kill, how to dehumanize someone in order to be able to kill him or her, and in doing so, how to of necessity dehumanize oneself. I still want to believe the “they” here refers to the enemy, but then I come to this line:

“Commander: Do you take hot sauce on those ashes?”

Part of the point here is that there’s little difference between “we” and “they,” and that “we” have little reason to persuade ourselves of any moral superiority.

Here, Stone steps back, providing temporary relief from the story’s intensity:

It’s May. Heat saps the water out of the body

as pines swoon in and out

and out. They have put aside the rabbit for me.

Commander: Gypsy, this is yours. Feed it. For now, feed it.

Some small choices in this excerpt are particularly effective, an article rather than a pronoun for instance: “the body” not “my body” as if the speaker is beginning to dissociate. The next line break, “pines swoon in and out / and out” emphasizes the heat’s dizzying effect. When the speaker is instructed to feed the rabbit, readers understand the possibility of emotional attachment but also notice the ominous “For now.”

As the poem develops, Stone emphasizes the role-playing nature of this class, focusing on the necessity of remaining in character. As the poem moves toward its climax, the significance of some details becomes clearer, and the speaker begins to understand her ethical dilemma. As an anthropologist, she might often be able to assert, accurately or not, cultural detachment, but here she is embedded, playing a game that is not play, within a culture that is at least to some extent her own. I am going to quote a long passage here in order to show how Stone conveys tensions among her “real” identity and her role, revealing eventually how little distinction there is between the two:

They bring me to the tree-line for kill class.

Gypsy this rabbit is yours. We have all been kind

enough to share our food and water out here.

We all have to help out so we can eat.

There is a pit for the un-useable

portions of the entrails. Secure the goat, slit its neck over

the pit, and proceed with the chickens.

This one is yours.

Use this stick. One time over

the head should be enough.

…

You have to, Gypsy, they say.

You can do it. Commander tries to give me

a fist bump to say We

are in this together. We are not in this together.

They cannot make me lift

my fist. Gypsy

how can we trust you? If you can’t kill

an animal, how

can you be a fighter?

The pines.

I’m sorry. I will clean it after if you want.

…

They bring me over the chickens warm and still

The flesh under

their feathers

the organs

pulled out / the pearled

interiors. This is meat now. I turn them

into something

we eat. I think I am done,

but Whisker says almost gently

Gypsy you need to kill the rabbit. Unfortunately

you do not have a choice.

I have a choice. Let me be perfectly clear,

I say. It is not happening.

The men make a circle

The pines make a circle

You need to hold

the legs. They are tying together

the legs the animal

screaming They raise

the stick The legs are in

my arms The legs are in my arms

What a conclusion. As insistent as the speaker has been that she has a choice, that she is different from the soldiers, that her role play remains more conscious than theirs, she discovers how implicated she nevertheless is, how implicated we all are. The most obvious sign that the speaker is losing control of her situation is the absence of punctuation in several of the lines toward the end of the poem. In addition, the line breaks and extra spaces between phrases create a confused and abrupt pacing, suggesting the speaker’s confused thought patterns. She acknowledges that she abstracts animals “into meat” by participating in their preparation after the kill if not in the kill itself, but she continues to insist, “I have a choice. Let me be perfectly clear, / I say. It is not happening.” Again, Stone’s reliance on a pronoun creates a useful ambiguity. On one level, the phrase is used colloquially, the speaker meaning that she is not going to follow the instructions she’s been given. On another level, the sentence is a plea of denial—this horror that is happening cannot possibly be happening. The poem ends with the rabbit not yet killed, though its imminent death is undeniable. The only question is whether the speaker will be able to remain a passive participant—though the poem certainly implies that she has already passed that point, that she passed that point even if unknowingly as soon as she entered this role play.

Kill Class is an unforgettable book. Its success depends on Stone’s ability to describe this material artfully, but as importantly, it also emerges from the speaker’s recognition of her own moral culpability in a world that repudiates any easy distinction between “us” and “them.”