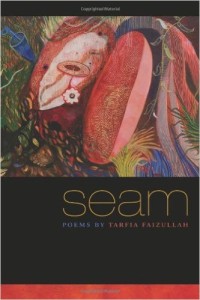

Seam. Tarfia Faizullah. Southern Illinois University Press, 2014. 65 pgs. $15.95.

Seam. Tarfia Faizullah. Southern Illinois University Press, 2014. 65 pgs. $15.95.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Seam, Tarfia Faizullah’s first collection, is that book many of us have been hoping for and the type of book some among us have probably tried and failed to write. Politically engaged without descending to diatribe, empathic without plummeting into sentimentality, Seam explores the effects of the 1971 war that led to the separation of East and West Pakistan and the establishment of the new nation of Bangladesh. Faizullah provides some historical context for the poems, most significantly the detail that military strategy included the rape of over 200,000 Bangladeshi women; the government later awarded these women the title of “birangona,” which translates as “war heroine,” though many of these women continued to experience shame and ostracization. The book explores the experiences of these women through the voice of an interviewer and of the women’s own voices filtered through hers. This book is successful as political poetry because it so directly addresses the horrifying experiences of some human beings through the systematic and willful behavior of other human beings; it is successful as poetry because the poet relies effectively on figurative language and exploits the possibilities of the line and stanza. Seam is structured not so much as a collection of individual poems as an extended meditation, a multi-part exploration of a single theme. The center of the book, for example, consists of eight sections titled “Interview with a Biragona,” interspersed with five poems called “Interviewer’s Note” as well as four other related poems.

The eighth section of “Interview with a Birangona” addresses the questions, “After the war was over, what did you do? Did you go back home?” In answering these questions, the speaker describes her reception when she did return home once, briefly. As with each of the other sections of “Interview with a Birangona,” Faizullah structures this poem in couplets, perhaps the most controlled stanzaic form, as a means of constraining some of the emotion, which might otherwise overwhelm:

I stood in the dark

doorway. Twilight. My grandfather’s

handprint raw across my face. Byadob,

he called me: trouble-

maker. How could you let them

touch you? he asked, the pomade just

coaxed into his thin hair

a familiar shadow of scent

between us even as he turned

away.

These opening couplets illustrate Faizullah’s ability to write evocatively even of such pain. The imagery is striking, her word choice not simply careful and precise, but unique. How differently line three would read with just a small change: “his handprint red across my face.” With “red,” the image would barely rise above cliché; with “raw,” we retain the visual image, but it also becomes tactile, and “raw” connotes not only anger but a coldly merciless response. A few lines later, Faizullah includes an image that in other circumstances could be nostalgic: “the pomade just / coaxed into his thin hair.” Here, “coaxed” is a particularly effective verb, implying a subtlety that pomade sometimes lacks. She relies on synesthesia next, “a familiar shadow of scent,” describing the aroma as visual, a “shadow” that evokes the real thing without being the thing itself. This olfactory image becomes the symbol not of grandfatherly affection but of rejection. Faizullah’s line breaks are equally effective. The pause between “dark,” concluding the first line, and “doorway,” beginning the second reinforces the speaker’s outsider status. The phrasing of the second line suggests that the doorway into the home proceeds through the grandfather, who will block it. Similarly, by breaking line four at the hyphen, rather than after the more syntactically logical “trouble-maker,” Faizullah emphasizes the speaker’s familial identity as trouble itself. The speaker’s grandfather orders her away, and she describes all she sees as she leaves, concluding with these lines:

…The dark rope

of Mother’s shaking arms was what

I last saw before I walked away.

No. No. Not since.

This last line answers the interviewer’s questions, but the answer is insufficient without the story that precedes it. And the story, through its precise rendering, is what readers remember.

Seam includes a few untitled prose poems, including the last poem of the book which I quote here in its entirety:

I struggled my way onto a packed bus. I became all that surged past the busy roadside markets humming with men pulling rickshaws heavy with bodies. A light breeze from the river was cool on our faces through the open windows. Eager passengers ran alongside us. The bus slowed down. A young man grabbed those arms, pulled them through. The moon filled the dust-polluted sky: a ripe, unsheathed lychee. It wasn’t enough light to see clearly by, but I still turned my face toward it.

The language of this poem suggests violence as much as it suggests hope—the “rickshaws heavy with bodies” rather than with people, for instance, or the man who “grabbed those arms.” Still, the speaker turns toward the light, dim and “dust-polluted” as it is. Having heard the stories of women who have survived experiences that seem nearly unbearable, the speaker has fulfilled a listener’s responsibility: to bear witness.

Faizullah tells these stories with grace and honesty, refusing to turn away but also refusing to exploit them through the inclusion of explicit violence that would only be gratuitous. Seam is not simply well-crafted; it is one of the most important collections published in these first decades of the 21st century.