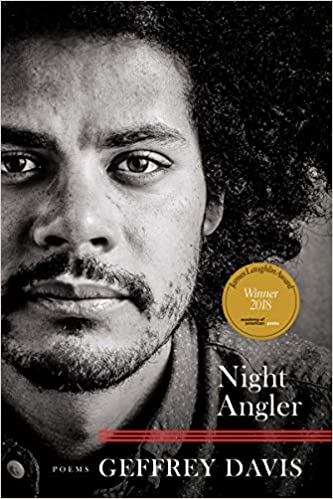

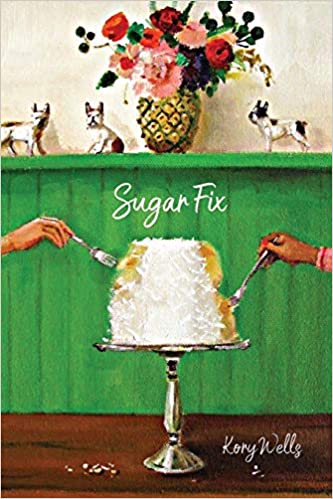

Kory Wells. Sugar Fix. Terrapin Books, 2019. 109 pgs. $16.00.

Sugar. Don’t we all love it. In chocolate, in cookies, in—as Kory Wells so wonderfully describes in one of her poems—red velvet cake. And don’t we all love that other sugar, that “I need a little sugar, Baby,” as Wells also explores in poems like “Dear Reader,” “Love Me Anyway,” and “He drove a four-door Chevy, nothing sexy, but I’d been thinking of his mouth for weeks.”

Sugar Fix, Wells’ first full-length collection, employs sweetness—and its absence—as a conceit to explore identity, ancestry, and the effect of the past on the present. The first few poems suggest that the collection will explore personal history and individual desire without wrestling with any of the social tensions of our time, but just as the reader relaxes into that belief, the poems begin to hint at that fact we all know, how personal history is inevitably entwined with all of the sins and failures of social and national history. One of the most admirable qualities of this collection—and the quality that really makes it a collection rather than simply an accumulation of forty or so poems—is how subtly Wells is able to weave personal ancestry with national history.

In many of the poems, Wells chooses a colloquial, idiomatic diction. The voice is often conversational without being plain-spoken, conversational, that is, without sacrificing personality. “He drove a four-door Chevy, nothing sexy, but I’d been thinking of his mouth for weeks” begins this way:

when he finally called me up

and asked if I’d like to get

some ice cream.

I was full from supper and my

thighs sure didn’t need it, but

I’ve never struggled with

priorities.

Already, we know what this speaker is about, and we know that she knows, too. There’s no circling around desire for her, no pretending she doesn’t want what she wants.

An element of craft that surprises me is how Wells uses the line, especially in stanza two. Ordinarily, I’d wonder if a poet who broke lines with words like “but” and “with” or even “my” had thought much about lineation. Wells clearly has, for throughout the rest of the poem, lines break with much stronger words, and as the poem heats up, she ends three consecutive lines with the word “him”: “I’d been praying about him. / How I wanted him, / how if I couldn’t have him, / I wanted to be free…” So what is she doing in stanza two? Ordinarily, in a sentence consisting of three independent clauses linked by coordinating conjunctions, which is the grammar of this sentence, both of those conjunctions, here “and” and “but,” would be preceded by commas. In this sentence, however, Wells uses a comma before “but” but not before “and.” The effect of this choice is that readers anticipate that whatever follows “my” will be another item the speaker is “full from.” So we are slightly surprised when the sentence turns to “my / thighs sure didn’t need it.” Reading this poem for the first time, I noticed my surprise and also my delight in it. The next clause, however, is preceded by a comma, so the “but” takes on more force. I was surprised and delighted again when I read “I’ve never struggled with / / priorities,” as the speaker reveals that self-discipline or restraint, characteristics we ordinarily value, aren’t considerations for her.

The poem continues in its colloquial way until we reach the final stanza:

I kept telling myself

it was just an ice cream,

but even then I knew

love is a kind of ruin.

When those cones arrived

so thick and voluptuous,

I almost blushed to open my mouth

before him, expose my eager tongue.

That ice cream, whether rounded mounds of chocolate fudge or swirls of soft serve, has come to represent all desire, and somehow we know that the speaker will be satisfied. “He drove a four-door Chevy,…” is a playful poem, demonstrating the fun we can have with language.

Other poems are more serious, especially those that explore the speaker’s Cherokee ancestry and questions of her extended family also including African American members. The history of race in the United States is decidedly peculiar, especially the detailed categories based on so-called blood quanta that were created by the legal system. In “The Assistant Marshal Makes an Error in Judgment,” Wells describes an occasion when one simple mark on a page utterly changes a man’s life. The poem begins with an extended sentence describing the marshal who is working in North Carolina soon after the Civil War. Mid-way through the poem, attention shifts to another man:

Assistant Marshal J.T. Reeves, who some call

carpetbagger, now sits amiably on the porch

with one Willis Guy, farmer, age 59,

and reads back to Mr. Guy

all he has written, so mistakes may be

corrected on the spot. The marshal is not

from around these parts, and Mr. Guy,

previously known as

Mulatto, previous to that known as

Free Colored Person, if asked would claim

Catawba, Cherokee, even the dark Porterghee,

but figures it best to keep his silence

as the government man’s ditto of Column 6. Like that,

Mr. Guy and all his kin become

White. Mr. Guy would admit he isn’t

as good at letters as his children,

but squinting sideways at the marshal’s ledger,

he knows the unmistakable difference between W and M.

So much is included here in these few lines. We don’t need to think too hard to realize that Mr. Guy’s appearance suggests he is white; only another marshal, one from the area and knowing Mr. Guy’s family, would know to write M. Though stating little directly, Wells is able to convey much. Even in a poem of this more serious subject matter, she retains her colloquial speech patterns, e.g. “figures it best,” “all his kin,” and “squinting sideways.”

Wells brings these themes together in “Some Notes and Three Word Problems on Red Velvet Cake,” one of the most ambitious poems in the collection. Divided into sections, the poem progresses through figurative and symbolic association rather than narrative, drops of food coloring linked to drops of blood, the law regulating each, DNA tests confirming some familial speculation. In this poem, sugar doesn’t simply satisfy a craving. The sweetness serves instead as a gesture toward racial reconciliation, though the poem also makes clear that the speaker’s family, and likely all families, have a long way to go before racial identities will not outweigh every other difference.

The poems in Sugar Fix reveal that Kory Wells is skilled with received forms as well as free verse, that she can tell her stories from multiple angles and in multiple ways. Few of the poems resemble each other on the page. This variety of form is particularly effective in a collection that continually circles its linked themes of desire and ancestry. Her story is certainly shared by many Americans, whether we acknowledge it or not, but her approach to that story is uniquely her own.