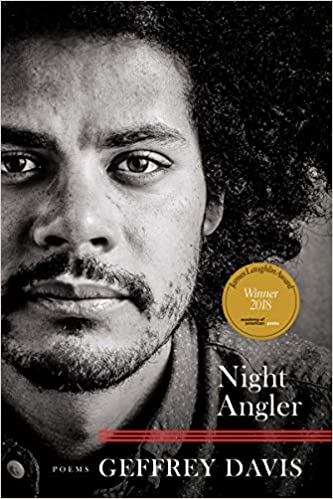

Geffrey Davis. Night Angler. BOA Editions. 2019. 96 pgs. $17.00.

Geffrey Davis’ Night Angler is a collection that is both absolutely timely and perfectly timeless, though its timelessness is unfortunate, or perhaps I’m pessimistic in calling it so. Many of the poems address the speaker’s challenges being a Black man in America, a Black father of a Black son. The poems are honest and clear-eyed, and they are also gentle. They explore the awe of fatherhood as well as its worries. The collection is successful for two primary reasons: the trustworthiness of the speaker, and the range of poetic styles and forms. Davis, in other words, has something to say and the skill to say it artfully.

One of the most intriguing pieces here is the multi-part poem, “3: 16,” a reference to the Biblical passage from the Gospel of John, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” Each section of this long poem takes its title from a word or phrase of this verse. Rather than use it as a weapon, as we so often experience in contemporary popular culture, Davis explores his associations with the words, taking the ideas seriously, as things to be understood, accepted or rejected, in terms of his own life, rather than as ideas so long received that they can reveal no new knowledge. The first section, “Whosoever,” is a ghazal, though there is so much else going on in the poem that the form becomes almost a counter-melody rather than an overly insistent beat that can sometimes occur in forms that rely on repetition. Here it is:

from the restaurant bar I smile & watch my only begotten sway

before the old musician who mirrors my only begotten’s sway

& strains to lift his bearded voice above the dining-room din—

they’ve paid him to play below conversation but my only begotten sways

two feet away from his blue guitar the grace of it giving him permission to push

his song out above the evening chatter in fact my only begotten’s sway

commands all eyes: the customers & young waitresses & old man fixed

even the purposeful darkness of the joint seems lit by my only begotten’s sway

so strange–: how open to perish we have become how freed from

first intent how surrendered to believeth only as my begotten sways

Davis takes some liberties with the ghazal—not every couplet is complete in itself, subject to rearrangement without obliterating the sense, and the repetend is not preceded by a rhyme. Davis’ revision of the form’s requirements, however, permit him to incorporate other strategies. I hear echoes of Langston Hughes (“He did a lazy sway… / To the tune o’ those Weary Blues”) and see perhaps an allusion to Picasso’s “old musician” playing a “blue guitar.” This section also includes several other words from John 3: 16, “perish” and “believeth.” And the dancing boy facilitates “grace,” both the musician and the diners experiencing themselves and the world anew: “how open to perish we have become how freed from / first intent how surrendered to believeth…” Davis doesn’t specify what exactly these people believe now—the poem is not doctrinal, not insistent on literalness, but mystical. He admits the strangeness of the experience, something that could neither be intended nor reproduced. Readers, too, if they are paying attention, will experience this poem’s mystery, for we are not directed what to feel or think but invited into the physicality of the music and the dance.

“Self-Portrait as a Dead Black Boy,” another poem consisting of multiple sections, several of them reminiscent of sonnets, adopts an entirely different tone, though it, too, is informed by the speaker’s identity as father. The poem references the Black boys and men whose names—Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and others—became known to Americans through their murders; one of its most discouraging effects is how long ago their deaths seem, not because they were long ago but because so many other Black people have been killed since.

The poem is thematically complex, opening with the speaker’s memories of shooting “minor things that wandered into yard” with a pellet gun. The first stanza ends with this line: “I could track if I had two surprised seconds,” while the second stanza begins, “to explain the meaning of my hands my instincts / would have been to show you the weapon / to turn hoping you could see gentleness.” Then it introduces Tamir Rice. The lineation here is especially effective, linking the speaker’s skill tracking small animals to the implicit quick reactions of someone who would, seeing the pellet gun rather than the young boy, mistaking Rice’s toy gun for deadly force, shoot back.

In section III of this sequence, the speaker himself, a father now, buys a gun, initially thinking it will protect him and his family. He realizes, though, that the gun is more likely to get him killed, directly or indirectly, than it is to save him. We’re not told what he does with the gun. Instead, we see him doing the only thing he believes he can do:

…on my knees

I’m preparing my heart to receive the next shots

until a new divinity forbids one more black body

be burned down…

Change will come only when “a new divinity” makes itself known, or, more accurately, when people recognize this “new divinity,” new, perhaps, not because it hasn’t existed but because it hasn’t been recognized. What is humbling here for white readers such as myself is that the speaker is “preparing my heart to receive the next shots,” preparing himself emotionally and spiritually for a most extreme injustice, rather than preparing himself for vengeance.

I look for the day when poems like this won’t be necessary. Right now, though, these poems are absolutely necessary, and I’m grateful that we have writers like Geffrey Davis to bring them to us.