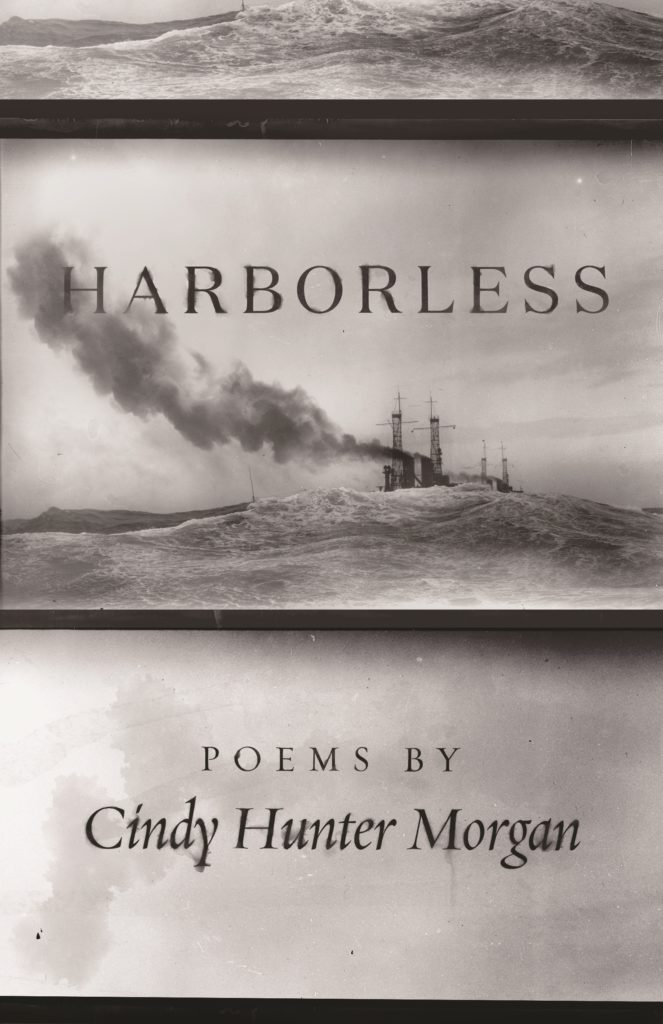

Cindy Hunter Morgan. Harborless. Wayne State University Press, 2017. 65 pgs. $16.99.

Harborless, Cindy Hunter Morgan’s first full-length collection, is unusual in several respects. The book consists of forty poems responding to specific shipwrecks on the Great Lakes, wrecks that often occurred because of weather, of course, but also due to exploding boilers, waterlogged wheat, or collisions with other ships. They carried loads of pigs, Christmas trees, apples, immigrants. The poems are interesting for their content but also for their craft—they rely on memorable figurative language, incorporate a range of poetic forms, and successfully incorporate the voices of multiple characters—yet they are also entirely accessible for readers who believe they don’t like poetry.

The collection is arranged into five sections, each bracketed by “Deckhand” poems that suggest thematic concerns to be explored in the following section. The first poem, for example, “Deckhand: Scent Theory,” describes a young man who recalls his past and considers his present through aroma:

When he climbed up the deck ladder

that first morning, his shirt still smelled

of his mother’s wash line:

Dreft and sunshine.

Now what he breathes is rain

and ore, deck paint, grease,

engine oil, boiler exhaust,

steam.

Mornings there is coffee.

Sometimes he pours a bit

on the cuff of his sleeve

so later he can press his nose in it.

The poem concludes with these lines:

At night he peels

his clothes off

and drops them in a pile,

dark, stagnant puddle

of stained cotton,

cesspool of sweat turning

to mildew.

The poem progresses from pleasant scents that recall presumably pleasant memories—laundry on a line and the deckhand’s mother—through less pleasant but utilitarian scents—deck paint, engine oil—to the unequivocally vile—a “cesspool of sweat.” This job, working on a ship all day out on the lake, might have seemed romantic to the young man when he was still imagining his future, but it quickly acquires the characteristics of most physical labor. It’s exhausting work, and the rewards are slight. The speaker doesn’t directly reveal the deckhand’s thoughts here, permitting the imagery to evoke all we need to know. Such effective imagery characterizes many of the poems in the collection.

These final two stanzas of “Deckhand: Scent Theory” also illustrate Morgan’s skill with sonic devices. We might quickly notice the slant rhyme between “peels” and “pile,” but then notice the repetition of both “p” and “l” in “puddle” one line later, as well as the subsequent internal slant rhyme with “pool” in “cesspool.” In addition the “oo” of “pool” is repeated in “mildew.” Because English spelling is so inconsistent, the same sound often represented by wildly different spellings, the carryover of “pool” to “mildew” is invisible to the eye and therefore more subtle when the ear picks it up. Then there’s also the alliteration of “stagnant” and “stained” which contribute to the consonance of “cotton,” “sweat,” and “turning.” And of course, there’s assonance in “cesspool” and “sweat.” Virtually every syllable, in other words, contributes to the aural pleasure of these stanzas. It’s tempting to assume that accessible poetry will be unsophisticated in its craft, but this poem more than manages the dual challenges.

Most of the poems in Harborless are written in free verse, but Morgan also incorporates several in received forms, notably a series of erasures printed to resemble the remains of burned paper, as well as a pantoum and a couple of prose poems. Here are the first few sentences of “J. Barber, 1871”:

Peach crisp, peach pie, peach jam, peach compote, whole peaches, sliced peaches. In those hours before the peaches burned, the whole ship smelled like August in a farm kitchen. The hold was full of Michigan orchards, full of juice and sugar and the soft fuzz of peach skin.

The exuberance of the opening list is fun to read, despite its context. The rhythmic energy continues throughout the poem, which concludes with this sentence:

Peaches sizzled and spit as the ship burned, as fire consumed what was made of sugar and what was made of wood, as masts toppled like limbs pruned from fruit trees, as men rolled across the deck like windfalls, bruised and scraped, and everything was reduced to carbon and loss.

Because of the exuberant language, the last clause, “everything was reduced to carbon and loss,” becomes particularly haunting, reminding readers that despite their visions of “men roll[ing] across the deck like windfalls,” this event is not comic but tragic. Morgan’s ability to manipulate the reader’s response is impressive here, as the poem includes such attractive imagery as “each peach was seared, the sweet juice of summer briefly concentrated and contained before everything cooked, oozed, dripped, and exploded,” appealing to the reader’s desire, before it turns to the final evocative statement.

This poem, like others I’ve discussed, achieves its effect in part through its reliance on imagery associated with the land, with farming, to describe its opposite, life on water. Morgan’s reliance on agricultural imagery creates an almost nostalgic motif woven throughout the collection, such that the poems have more subtle craft-oriented relationships in addition to the obvious relationships of content.

The cities of Marquette and Munising, MI, both located on the shore of Lake Superior, have chosen Harborless as one of their community reads for next fall. A collection of poetry might be a daring choice for such a program, but this book is exactly the collection to appeal to experienced readers of poetry as well as readers who believe they don’t like poetry. Its content is compelling and its characters are sympathetic, as in the best fiction, yet its craft is both skillful and subtle. Reading and rereading this book has been exceptionally satisfying.