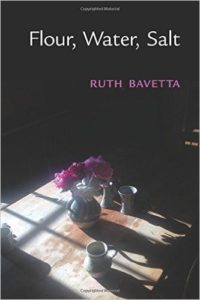

Ruth Bavetta. Flour, Water, Salt. FutureCycle Press, 2016. 73 pgs. $15.95.

Ruth Bavetta. Flour, Water, Salt. FutureCycle Press, 2016. 73 pgs. $15.95.

The titles of the poems in Ruth Bavetta’s most recent collection, Flour, Water, Salt, will certainly pique the interest of most readers: “If I Were a Maker of Marzipan,” “Grandmother’s Bird’s Nest Pie,” “More Than Thirteen Lemons in the Rain,” “A World with No Chickens.” These titles suggest an imagination that is attentive to the world, to its detail, and one that is also engaged with language. These characteristics are born out in the poems, which consider the rituals of daily life, particularly of food and cooking, meals eaten with family members, the bodies that are nourished in kitchens.

The collection is organized into three sections named with the three nouns of the title. Several poems in each section somehow incorporate the subject, creating a thoughtful coherence, but the approaches are unique and intriguing, analogous to a collection of related short stories in which the protagonist of one might appear only as a fleeting pedestrian in another. The reader begins to anticipate the appearance of flour or water or salt and remains aware of the connotations of these necessities even when the poems don’t mention them directly.

Among the most successful poems in the collection is “More Than Thirteen Lemons in the Rain,” written “after Wallace Stevens.” Through its startling imagery and associative organization, this poem demonstrates the influence of Stevens’ famous thirteen ways, but its references and connotations are less obscure than in much of Stevens’ work. The poem is composed in couplets, each of which could stand independent of the others, but the accumulation of imagery contributes to a more pronounced effect than any individual couplet could. Here are the opening stanzas:

The tree, not in an orchard

but alone in an overgrown garden.

The fruit, brilliant

on this grey day, each one its own sun.

Lemon after lemon after lemon,

all the same, yet none the same.

Sour surrounded by bitterness

surrounded by light.

We see the tree first amid disorder, and then we see the fruit as light amid darkness. Couplets are perhaps the cleanest and most crisp stanzaic form, especially when each second line is end-stopped. Immediately, therefore, the poem brings order to the overgrown chaos of the garden, and to the almost profligate abundance of the tree, the “Lemon after lemon after lemon.” The poem is embedded with paradox—not only order and chaos or “brilliant” yellow against a “grey day,” but sweet and sour, wine and lemonade. The speaker refers to human beings in only three of the eleven stanzas, including two of the most memorable, stanza five: “He thought it was a ball until / the fragrance stained his fingers” and stanza nine: “Blood running down my mother’s arms, / the lemon’s thorns.” A lemon distinguishing itself as lemon through “fragrance” is not surprising, yet it is startling in the context of this stanza, when it is unrecognizable as fruit or even as living object until “He” smells it. This couplet prepares the reader for additional references to human engagement, but we are unprepared for the implicit violence in stanza nine. Aside from the “grey day” in stanza two, the poem overflows with yellow and yellow and yellow—shining bright warmth. Then in stanza nine, and only in stanza nine, we see a color that is equally bright and warm. Unlike lemon juice, however, blood is neither sour nor bitter but intimates passion and danger. This poem would have been memorable even without stanza nine; with it, the poem is haunting.

Bavetta exploits concrete imagery throughout this collection; her skill with imagery is perhaps her greatest strength. The poems are most successful when she permits the imagery to imply metaphor or to suggest significance. In some of the poems, the metaphors—especially as constructed “the x of y” with “y” and abstraction—feel self-conscious and even unnecessary: “whipped / into a meringue of longing” (“Queen of Puddings”), “dredged in the flour of expectation” (“Honeymoon”), “Drank the water of discontent” (“What We Did”). Some of these metaphors would be stronger if they were implied, e.g. “dredged in expectation” or “drank discontent.”

Flour, Water, Salt is a thoughtful collection whose arrangement creates a narrative of relationship. The tone is often compassionate, even when the speaker expresses anger or explores bitterness. That is, she treats others, including an ex-husband, fairly—although he’s described negatively, the speaker most often includes herself in her critique. In its entirely, the book is an exploration of anger and joy, hope and sadness that equates, ultimately, to acceptance.