![]()

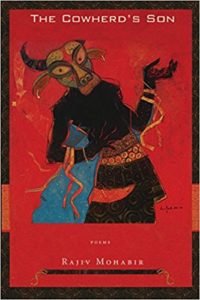

Rajiv Mohabir. The Cowherd’s Son. Tupelo Press, 2017. 99 pgs. $16.95.

Rajiv Mohabir. The Cowherd’s Son. Tupelo Press, 2017. 99 pgs. $16.95.

The Cowherd’s Son, Rajiv Mohabir’s second full-length collection, is filled with references to Hinduism and India. Readers encounter Krishna, Sita, the Ganges river, Holi, Kolkata, curry, and henna—as well as colonialism, Coca Cola, New York City, and Hawaii. To many American readers, the collection will initially feel, therefore, remote or even alien (or worse, exotic), for though American culture has become increasingly diverse over the past two or three generations, it has also become profoundly secular. We may eat more tandoori or masala, more pad thai or pineapple fried rice, more falafel and tabouleh, but the average American’s knowledge of non-western religious traditions is probably not much more extensive than it was in 1950. Yet these poems are written with such precision—Mohabir’s attention to craft is so detailed—that readers will return, intrigued, even if they remain also for a time confused, because the language is so attractive.

Mohabir’s incorporation of traditional Indian cultural content succeeds because he treats it dynamically. Rather than simply describe Krishna or retell an ages-old story, he connects tradition to his speakers’ own lives. The past seeps into the present, for tradition is on the one hand explicitly concerned with time, connecting ancestors and descendants; yet tradition also transcends time, suggesting that these things we do and believe ever were and always shall be. Inasmuch as The Cowherd’s Son addresses and confronts tradition, therefore, it is about connection.

“Holi” opens with these couplets:

Coward, how can you warm your hands

so far from the Holika in flames?

Come closer and trace the subway and ship

lines in these palms. You gather embers

in your dustpan to light your own fire

and dream of the return of some god

who will pull you from this coolie history

unscathed,…

Holi is a Hindu spring festival, the festival of colors, which begins during one evening and continues through the next evening. As the festival opens, celebrants pray before a bonfire that evil will be destroyed, including their own evil, burned as the ancient figure Holika was burned. This poem relies on images of fire and heat, juxtaposing details of the tradition against details of modern life. The speaker is both being warmed by coals and in danger of being consumed by fire, unless “some god” pulls him “from this coolie history.” The poem develops through an accumulation of allusions to the Holi narrative, and then concludes:

Cowherd, can you pray, your tongue

so cleft, or do you eat the coals

to cauterize the mantras flapping

wild as cicadas in your hollow?

Look around at beauty cloaked

in orange. Everything you love

will one day burn.

This last sentence, which in another context might be read as a threat, is here reassuring instead. The cycle of living and dying will continue, and we will each be consumed. The poem shifts at the beginning of this second quotation, turning toward different questions and answers than the speaker had provided at the beginning. Yet the turn is not absolute, as we hear in the near repetition of “Coward” and “Cowherd.” “Cowherd” also opens onto a series of alliterative words—“can,” “cleft,” “coals,” “cauterize”—particularly attractive to the ear. The simile that follows, “wild as cicadas” (with the internal hard c in “cicadas” not technically alliterative but creating nearly the same sonic effect), initially strikes me as odd, for I don’t usually associate cicadas with wilderness. As I consider the simile further, I think also about the “mantras,” those words or phrases meant to keep us focused. How, or when, is a mantra like a cicada? Or, what happens when a mantra becomes undifferentiated noise? Isn’t that what mantras are intended to be, more sound than meaning?

The next line contains another alliterative hard c in “cloaked,” and this line break is especially effective, as the line suggests that beauty is disguised until we cross over the line break to the end of the sentence, “in orange.” We see again the beauty of flame. Everything will burn, but fire and smoke rise and disperse, becoming not nothing but a part of everything. The embers remain for a time, able to reignite the fire, just as cicadas seem to crawl from the earth, alive again after a period of dormancy. The language of this poem is beautiful, and its ideas are evocative. Attentive readers will mull it over, returning to it again and again, attracted by its refusal ever to have its meaning completely resolved.

Many of the poems in The Cowherd’s Son enact a similar puzzlement over meaning. “Cow Minah: Aji Tells a Story,” is structured in several sections, each section narrated in English and a patois. “My Name is a Map” is also arranged into four sections, each exploring connotations of one of the speaker’s names—“Paul,” “Raimie,” “Rajiv,” and “Mohabir” or “Mahabir.” “Mysterious Alembics” consists of eight brief sections of prose that together explore relationships among caste, sexuality, geography, family, and language.

Reviewers often look for some weakness to cite, as if to prove our objectivity or our distance from the author. Here there are none. Individually, each of the poems in this collection compels rereading. Together, they present a complex portrait of a person whose position in the world seems unstable but only because it is so intricately layered.