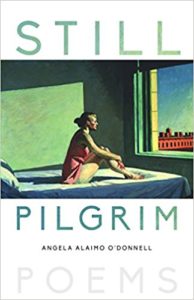

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell. Still Pilgrim. Paraclete Press, 2017. 77 pgs. $18.00.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell. Still Pilgrim. Paraclete Press, 2017. 77 pgs. $18.00.

The first thing readers might notice about Angela Alaimo O’Donnell’s latest collection, Still Pilgrim, is that the title character is an ordinary (if more attentive than some) woman meandering through this ordinary (and yet extraordinary) world. She is observant and devoted and also witty. Hurtling through space at thousands of miles per hour, her world seems to preclude stillness, yet she seeks it nevertheless and occasionally even finds it. Her outer world, in which she watches her mother undress and later dresses her own son, reads poetry and visits museums, listens to Frank Sinatra and fries pork chops, guides her pilgrimage inward. This collection confirms what every pilgrim learns—every journey is a journey to the interior.

The poems are near-sonnets (she refers to them as sonnets, but I am more curmudgeonly conservative on these matters), 14 rhymed lines close to iambic pentameter. Through the collection, the poems demonstrate how flexible a form the sonnet can be. Despite the consistent iambs, O’Donnell’s rhythm varies through strategically placed caesuras, polysyllabic words juxtaposed against monosyllabic ones, hard consonant sounds interspersed among softer ones. The rhymes, too, vary in tone, from somber to hopeful to humorous. The variety O’Donnell exhibits within the comparatively restrictive form mirrors the construction of the speaker, always identified only as “the pilgrim” but nevertheless developed as a round character with moods and worries and insights, successes and failures.

Here is the opening stanza of “The Still Pilgrim Tells a Fish Story”:

Find the fish you need to kill and kill it.

The Moby Dick of your life. The one who

keeps running away with your line. Chill it

on ice, then eat it cold, smoked, and blue.

This is the way you have your way with it

after it’s had its way so long with you.

The imperative mood of the opening line is enhanced by its ten consecutive monosyllabic words, including the repetition of “kill.” The sentence, reproduced as the line, is emphatic. The rhythm slows a bit in the next two lines, in part because they contain three words of two syllables each, but also because the sounds of the words are softer, and their grammatical functions are less insistent—the two consecutive prepositions in line three for instance. Line five approaches the force of line one—and its structure is quite similar—but it is immediately and effectively undercut by line six. We get the sense that the speaker won’t turn out to be as triumphant as the stanza wants to suggest. The second stanza confirms this impression:

Yet even once you kill it, it will still

haunt your dreams, aim its skull at your small boat,

batter your bow till it shatters, spill

the sea into your world and down your throat.

By night, at the mercy of the same fish

whom you dispatched and served upon a dish.

Did you really believe there’d come a day

when you would be the one that got away?

With the repetition of “kill it,” the first line of this stanza recalls the first line of the poem, its meaning emphasized by the insistent internal rhyme: “kill…will still.” “Still” here also evokes the “still pilgrim,” though in this poem her spirit seems anything but still. The pattern of rhyme means that we’ll notice one more instance two lines later, “spill,” but again that line contains an internal rhyme with “till.” The line between includes the off rhyme of “skull.” The sonic effects are appropriately forceful, aligned with this content, an obsession, a haunting, of a person determined to rid herself of “the fish” she needs “to kill.” Obsessions can never be truly killed, of course, as Melville’s novel teaches us. The last lines respond to the colloquial expression, “fish story,” in the title: “Did you really believe there’d come a day / when you would be the one that got away?” She will never, in other words, get away. Perhaps the “fish story” is the one she’s told herself—that she could get away.

Ironically, pilgrims don’t generally try to escape their obsessions but rather walk toward them. Those who flee end up like Jonah, awash in the stinking bodily fluids of the beast that will force them to face their calling. Pilgrims aren’t necessarily prophets—through their more contemplative practices, they can often seem the opposite of prophets—but the two roles share at least one characteristic, the near impossibility of being declined.

Some of the poems are more light-hearted, and among my favorites is “The Still Pilgrim’s Refrain.” This poem exploits the line breaks to build anticipation, repeating a single word at the beginning of each line, the reader’s delight increasing with each instance. Here is the poem in its entirety:

Home again and most like home

is the need to leave and return

again, the sojourn fun and done

again, and now my life’s my own

again. I wake up in my bed

again, make up my day from scratch

again, give thanks I am not dead

again, make sure my two shoes match

again, and walk into the world

again, set foot upon the path

I’ve walked so many times before

again. I will not do the math.

Again I sing my pilgrim song.

Again I am where I belong.

Is a pilgrim simply a restless soul, unable to sit still, to take a vow of stability, a mendicant rather than a monastic? Perhaps. But this pilgrim recognizes her pattern of departure and return, the rhythm created by walking the same path. By the end of the poem she recognizes the foundation of her calling, not to go where she is not, but to be where she is.

O’Donnell includes an afterword that I found particularly insightful in its discussion of the origin of these poems. Her description of her visit to Melville’s grave reveals something we readers often know but seldom accept—the coincidental, associative, and indirect nature of artistic inspiration. These poems do have an autobiographical origin, but as with much art, it’s not what many readers might predict.

The book is also one that readers might not predict, featuring a speaker who can be serious about her faith without being dogmatic, who is comfortable with paradox, who trusts that her life has meaning even when that meaning remains partly obscured.