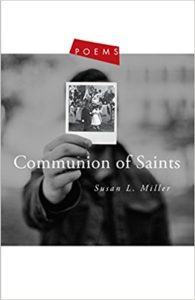

Susan L. Miller. Communion of Saints. Paraclete Press, 2017. $18.00.

Susan L. Miller. Communion of Saints. Paraclete Press, 2017. $18.00.

Communion of Saints, Susan L. Miller’s first collection, is arranged into four sections, “Faith,” “Hope,” “Love,” and “Pax et Bonum,” a phrase which translates as “peace and all good” and is particularly associated with Francis of Assisi and Franciscans. This last section contains poems inspired by a pilgrimage the author took to Assisi. The other three sections consist primarily of poems connected by a conceit—their titles link an acquaintance of the speaker with a saint, e.g. “Portrait of Sister Carol as St. Cecilia” or “Portrait of Ann as St. Stephen, Martyr.” This device could grow old, functioning more as a gimmick than a driving force. Fortunately, Miller knows what she is doing; the links between the titular figures are neither superficial nor simplistic; the appropriateness of the figurative identities is revealed gradually and emerges from the details of their lives. Miller does provide notes identifying pertinent details regarding the saints, but the poems could, in fact, be read without any prior knowledge, though familiarity with the saints’ lives certainly deepens appreciation of the poems. Some of the saints she mentions—St. Francis, St. John the Baptist—will be familiar to almost any reader; others—St. Agnes, St. Anthony of Padua, St. Bonaventure—will be familiar to most devout Catholics; a few—St. Roch, St. Pascual Baylon—might be entirely unfamiliar to almost all readers. Yet the poems do what literature does best, make the readers want to know more.

The collection opens with a poem placed as prologue, “Manual for the Would-Be Saint.” Miller provides instructions that apply to the dailiness of what it means to be human, those moments when so much harm can be done, as well as to those experiences of transcendence we so often associate with saintliness. Here are the opening lines:

The first principle: Do no harm.

The second: The air calls us home.

Third, we must fill the bowls of others

before we drain our own wells dry.

The fourth is the dark night; the fifth

a subtle scent of smoke and pine.

The sixth is awareness of our duties,

the burnt offering of our own pride.

Seventh, we learn to pray without ceasing.

These lines illustrate both Miller’s perception of saintliness and her attention to craft. Some of the lines allude to Biblical language or to writings of saints, “the dark night,” “burnt offering,” “pray without ceasing.” Even in these lines, though, she suggests that holiness occurs through actions that might be more difficult than we anticipate; the “burnt offering” we are called to offer is not a sacrificial animal but “our own pride.” Other lines suggest that these saintly qualities occur in the context of incarnation; human life is imminent as well as, we hope, transcendent: “a subtle scent of smoke and pine.”

The content of this poem is thought-provoking and will easily appeal to readers invested in spirituality; the form offers lessons to any poet invested in craft. Of these nine lines, seven are end-stopped; of the entire poem’s twenty-six lines, in fact, nineteen are end-stopped. Yet the rhythm varies significantly from one line to the next, primarily because Miller includes caesuras at different points in the lines. In line one, the caesura occurs between syllables five and six; in the second, it occurs between syllables three and four; and in the third, it occurs after the first syllable. Miller achieves this by relying on modest anaphora, the suggestion of repetition without its full weight—“The first principle,” “The second,” “Third.” By the time we reach line five, Miller begins and ends the line with the numeric signals, “The fourth” and “the fifth.” Miller’s strategies throughout these lines permits her to exploit syntactic devices without risking monotony.

Just when Miller has extended this strategy about as far as it can be extended, the poem shifts direction again:

Eighteenth, we enter the stranger’s city

at the mercy of the stranger’s hand.

Nineteenth, love flees the body,

and the spirit leaves its husk. And suddenly

the numbers do not matter: nothing that is matter

matters anymore: all is burned, all is born,

all is carried away in the wind.

This conclusion is satisfying on several levels. It demonstrates that all of these instructions, expected and unexpected, have been leading toward something greater. Miller plays with language, punning on “matter,” that substance we often mistake for the opposite of spirit. And finally, the imagery suggests that the way to sainthood transcends not only “matter” but also religious distinctions, for those last two lines could have as easily been spoken by a Hindu or a Buddhist. Sainthood it seems according to this “Manual” is not achieved so much as simply experienced.

Perhaps this is one reason why Miller is able to ally so many of her acquaintances with saints. In “Portrait of Evie as St. Martin de Porres,” she describes her friend and colleague, the poet Evie Shockley, speaking with commitment and grace, revealing that power can reside apart from domination:

….And she writes, we too: specific,

in every hue, the human family emerges and recedes

like the patterns behind eyelids when I close

my eyes. San Martin taught this kind of grace:

when called by royalty to heal the sick, he arrived,

knelt, and queried, Why would a prince have need

to call on a mulatto, a poor friar like me? Then,

knowing his powers exceeded anyone’s

in that room, he laid his hand on the man’s flesh

and healed him.

The line breaks in the last full stanza are particularly effective. We pause after “Then,” lending the syllable additional weight, until the “poor friar” does what he has come to do. Breaking the next line between “anyone’s” and “in that room” permits the prepositional phrase to do double duty—St. Martin has more power than anyone in the room, and it is also “in that room” that “he laid his hand on the man’s flesh // and healed him.” Miller doesn’t often indent lines as she does with the final one here, but the additional pause reinforces the effect of the saint’s action. We are left with the suggestion that St. Martin might have healed the prince more fully than the prince had hoped. He is presumably healed of his physical illness but perhaps he is also healed of the spiritual wounds that encourage him to draw distinctions between himself, the prince, and St. Martin, the mulatto.

Miller’s poems are ambitious, perhaps even more so collectively than they are individually. They show us what poetry can do, encouraging us to notice grace-filled people in this grace-filled world.