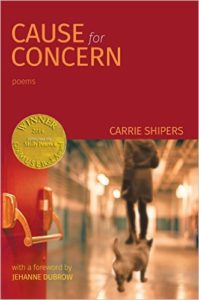

Carrie Shipers. Cause for Concern. Able Muse Press, 2015. 84 pgs. $18.95

Carrie Shipers. Cause for Concern. Able Muse Press, 2015. 84 pgs. $18.95

Carrie Shipers. Family Resemblances. University of New Mexico Press, 2016. 70 pgs. $17.95

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Carrie Shipers’ second and third collections of poetry appeared within a few months of each other, and I read them within a few days of each other. Stylistically, the poems in the two collections are similar—most careful readers would with reasonable confidence identify them as composed by the same author—but they differ in theme and tone. The first, Cause for Concern, explores Shipers’ experience as primary caregiver for her husband as he recovered from kidney surgery, while Family Resemblances includes a broader range of material, though many of the poems examine the speaker’s position within her family of origin. In both collections, the poems rely on implicit or explicit narrative, comparatively even line lengths—though the lines nevertheless contribute substantially to the rhythmic interest—and language that is interesting yet direct. Both collections include a series of poems scattered throughout—in Cause for Concern it’s a sequence of haunting dog poems, and in Family Resemblances it’s a sequence of poems narrated by “The Woman Who Can’t Forget” (one of which was recently featured on Verse Daily)—that function as commentary on the poems that surround them. Throughout the collections, the speaker’s reliability is provocatively questionable, but her character is also reassuringly familiar. Like it or not, we’ve all been this speaker.

Despite the often somber content, the poems do contain some humor. “Field Guide,” for example, from Family Resemblances, reveals how the certainties of a relationship can become both less certain and more interesting: “She married him for what he knew— / names of trees, animals, how to hot wire / his Mercury…” She is gullible, however, or naïve, or both: “They had three kids before / she caught on.” Shipers delays the reader’s gratification for a few lines—“caught on” to what? Revealing the answer to that question, Shipers shifts from the names of birds to other names: “Did he make up socket wrench? Phillips head?” The husband has been answering all along, but his responses have included more fantasy than fact. The stanza breaks here, at approximately the 2/3 point, and the beginning of stanza two becomes more serious. The speaker also fantasizes,

Despite the often somber content, the poems do contain some humor. “Field Guide,” for example, from Family Resemblances, reveals how the certainties of a relationship can become both less certain and more interesting: “She married him for what he knew— / names of trees, animals, how to hot wire / his Mercury…” She is gullible, however, or naïve, or both: “They had three kids before / she caught on.” Shipers delays the reader’s gratification for a few lines—“caught on” to what? Revealing the answer to that question, Shipers shifts from the names of birds to other names: “Did he make up socket wrench? Phillips head?” The husband has been answering all along, but his responses have included more fantasy than fact. The stanza breaks here, at approximately the 2/3 point, and the beginning of stanza two becomes more serious. The speaker also fantasizes,

…by pretending

to know what she only hoped, each time hoping

he’d catch her out so she could tell the truth:

I’m scared too.

Telling the truth often is a relief, and the truth the speaker is able to acknowledge demonstrates Shipers’ skill in exploiting an anecdote to reveal the poem’s own deeper truth. By its end, the poem circles back to its beginning, with the speaker asking about a bird and her husband stating, “Three-toed warbler.” What began years earlier as curiosity and play has grown into ritual, a practice that in its simplicity sustains the relationship. The poem circles back to its beginning, but that beginning has acquired more significance. Looping back this way, tying the poem’s final image to its first, is a common strategy that, in successful poems, redefines the opening. Through these twenty-three lines, readers understand how the speaker has grown through decades.

The primary factor in the success of “Field Guide” is its structure. But Shipers is also skilled in other areas of poetic craft—choices made at the level of word and line to enhance rhythm and image. Although the poems are most often free verse, the lines are informed by English poetry’s iambic history; they are not shackled by a compulsive adherence to regular meter, but the echo of meter is suggestively pleasant. Here is the last couplet of “Appetite,” a disturbing response to the tale of Hansel and Gretel: “And while I talk I’ll dish up supper—black pudding, / potatoes, a roast as sweet as suckling pig.” The first of the lines begins with three iambic feet which are interrupted with syllables “up supper” that include an internal rhyme, with the “p” repeated two syllables later and then repeated again at the beginning of the second line. Following “potatoes,” the final line returns to an iambic meter, emphasized again with alliteration and assonance. Other lines adopt similar strategies, and they are able to do so because of Shipers’ reliance on concrete, often monosyllabic vocabulary. The creepiness of this poem’s content is ironically contradicted by its pleasing music.

The poems in Cause for Concern are also memorable for their concrete imagery—one would hope, of course, that poems describing sick and wounded bodies would be concrete. The opening poem, “Wound Assessment,” alternates between references to Doubting Thomas, as he’s often called, reaching into Christ’s wounded side, and descriptions of the speaker changing the dressing on her husband’s surgical wound. The speaker here isn’t an idealized nurse but an afraid and resentful young wife. Everything begins to signify her husband’s illness, from scissors to her dining room table. Her husband’s wound is as obvious as Christ’s, but the speaker’s wound is as invisible as either doubt or belief. The poem succeeds, like “Field Guide” which I discussed above, in part because of its structure, the references to Thomas woven throughout, and also because of the language itself, particularly the verbs.

Both of these books are provocative. In Cause for Concern, the speaker acknowledges unattractive, if understandable, traits. Some readers will empathize with her response; others will not. As in fiction, it’s much more difficult to write well of an unsympathetic speaker than of an attractive one. These poems raise ethical questions, not only about marriage and the care we owe each other, but also about the responsibility of the writer, which must include a commitment to truth, especially when it’s a truth, like resentment of a spouse’s suffering, we would rather not acknowledge. The speaker in Family Resemblances is generally more sympathetic, but the family dynamics explored are nevertheless also often troubling. We could say the same about many poems, of course, including many badly written ones. The content of Shipers’ poems is interesting, but it’s her craft that’s most admirable.