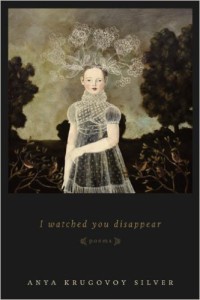

Anya Krugovoy Silver. I Watched You Disappear. Louisiana State University Press, 2014. 73 pgs. $17.95.

Anya Krugovoy Silver. I Watched You Disappear. Louisiana State University Press, 2014. 73 pgs. $17.95.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Like many readers, I found Anya Krugovoy Silver’s first collection, The Ninety-Third Name of God, published in 2010, absolutely stunning. I waited impatiently for her next collection, I Watched You Disappear, and eagerly read it when it was published a few months ago. The two books share several themes, especially the speaker’s relationship with God and the effects of living with cancer. I Watched You Disappear is the more somber of the two, as the speaker’s community seems to absorb one death after another, and it more predominantly focuses on death and grief. This collection is more emotionally difficult because of death’s relentless hovering and so harder to read straight through, but the poems are just as accomplished and memorable as the ones in Silver’s first collection.

“Night Prayer,” the second poem in the collection, is stylistically representative of many of the poems in the book. At fourteen lines, it gestures toward the sonnet, with some iambic stretches in the lines though no absolute iambic pentameter, and with some near rhyme though no pattern of true rhyme. If there is a turn in this poem, it is slight and occurs after line ten, or maybe even line twelve, rather than following an octave. Still, the poem takes prayer as its subject, something that can be turned over and examined from multiple angles, relying on imagery and metaphor rather than narrative to drive it forward, and it concludes with a couplet (though the poem is arranged as one stanza) that clicks closed with the finality common to sonnets. Many of the lines seem to question not only the efficacy of prayer but also the existence of an always apparently silent audience. The poem opens this way:

I talk and talk and hear nothing back.

You who are neither voice, nor sign,

nor image. In answer to my pleas,

not the slightest flutter of humid air

or pause in cicadas’ raspy vespers.

According to this poem, prayer is what makes nothing happen. Not only does God fail to respond, but the speaker’s environment is so uniform from one minute to the next that she can’t interpret any event as a sign even if she’s determined to.

If nothing happens around the speaker, however, something does happen within the poem. The first line begins iambically, and it contains the near rhyme (or at least a sonic reference) of “talk” and “back.” With seven of its eight words being monosyllabic, this line sounds insistent, and the insistence carries into the first half of the next line. By sentence three, however, beginning in line three and carrying through line five, the pace slows, with softer sounds and substantially fewer monosyllables. Rather than the hard sound of “k” repeated three times, line five renders its meaning through the thrice-repeated “p.” Because Silver has slowed the pace, the reader becomes prepared for a more reflective consideration of the speaker’s experience, as eventually occurs. The next lines reproduce some of the sounds we notice in lines four and five:

No stutter of starlight, no pillow

slipped beneath my knees or swallow-

tail alighting on my waiting hands.

Line six develops through true alliteration—“stutter of starlight”—and moves into the closest example of true rhyme in the poem, “pillow” and “swallow.” In addition, “slipped” extends this section of the poem’s reliance on “p” and “l” to maintain the slower rhythm. In terms of content, the imagery reinforces the statements in lines one through three suggesting God’s absence. Because of its mastery of craft, the poem has been pleasurable to read throughout, but the final two lines provide the most satisfying surprise. I, at least, was expecting some sort of resignation if not outright anger from the speaker, but instead she closes with an acceptance that reminds us, through image as well as denotation, of her connection to God:

And what I speak remains traceless—

like a beetle’s breath, this Amen.

The speaker’s words leave as little evidence of their existence as the God whom the poem addresses, and in this way the speaker resembles her audience; she is an “image” that was called absent in line three. Her last word, “Amen,” concluding the prayer, reinforces the speaker’s status as creature rather than would-be creator, as understanding and accepting her identity in terms of the divine.

A poem toward the end of the collection, “Portraits in the Country,” adopts a similar strategy at its conclusion. Several of the poems in this last section of the book are ekphrastic, and Silver provides an identification here: “Gustave Caillebotte, 1876.” The poem responds to Caillebotte’s painting, Portraits à la Campagne, in which four women relax in a park, doing needlework or reading. The speaker associates herself with them as she proceeds through time without the hurry or rush or busyness so characteristic of our era. Instead, she says,

I am shutting my ears to the hours,

to the bell tower’s quarterly reminder

that I should be doing something useful.

Usefulness can be valuable, but it does not constitute the total meaning of our lives. This speaker chooses attentiveness and meditation:

For death has come to our windows,

the preacher says, it has entered our palaces.

But I will not rush to push down my sash.

Instead, I will turn the leaf of my book.

Here, the speaker refuses to deny what she knows, death’s undeniable presence, but she also refuses to permit that knowledge to consume her. Again in these lines, Silver creates part of the effect through sound, here the repetition of “sh”: rush, push, sash. The poem would be perfectly fine it if concluded with this line, but Silver extends it with a surprising turn similar to the one in “Night Prayer”:

See with what gentle gravity God

lets it hover, in balance, then fall to its side.

These poems call their readers to share in their reflection. They don’t demand rereading as more elusive poems sometimes do; instead they invite rereading through the hospitality of the tone and language. Of course, now, I am looking forward to Silver’s next book. But I am also content to wait, for the poems we have already in her first two collections welcome our lingering.

——————————————————

To propose a guest review or submit a book for review consideration, send a message to lynndomina (at) gmail.com.