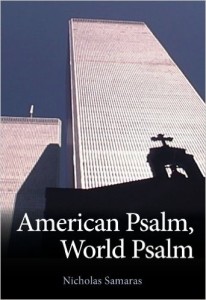

Nicholas Samaras. American Psalm, World Psalm. Ashland Poetry Press, 2014. 233 pgs. $22.95.

Nicholas Samaras. American Psalm, World Psalm. Ashland Poetry Press, 2014. 233 pgs. $22.95.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Nicholas Samaras’ second collection, American Psalm, World Psalm is a hybrid book, though not “hybrid” in the sense that we often hear the word applied to contemporary literature. It’s not the offspring of prose and poetry, of memoir and fiction, or of print and electronic text. It is, instead, a hybrid of psalm and poem. Those two aren’t entirely distinct genres, of course, since psalms are by definition poems, though the reverse is not true. Yet psalms in their canonical sense share particular characteristics even as they can be further classified as psalms of praise, psalms of lament, imprecatory psalms, historical psalms, etc. The most common linguistic feature of Biblical psalms is their use of parallelism, e.g. “I will give thanks to you, O Lord, among the peoples, / I will sing praises to you among the nations” (Ps. 108:3). Consistent parallelism as a formal trait is rare in contemporary poetry in English, though canonical psalms also rely on the types of figurative language we also expect in other types of poetry, e.g. “The Lord is my shepherd” (Ps. 23:1). In these modern psalms, Samaras doesn’t rely on the parallelism so characteristic of their Hebrew kin; nor do these psalms always respond explicitly or directly to those in the Bible. Yet American Psalm, World Psalm contains 150 entries, just as the Book of Psalms does, and Samaras’ collection is arranged into five “books,” just as the Book of Psalms is. And Samaras’ psalms are prayers as much as poems, with God clearly among his intended audience. A few of the pieces in this collection do succeed more as prayer than poem (odd as it is to suggest that prayers “succeed” or not), but I will focus here on the psalms that are also most effective as poems.

The poems in this collection vary in form—couplets, quatrains, single long stanzas; rhyme and free verse; litanies and blues. They also vary considerably in length, though the average might be about a page. Yet they are consciously products of their time, containing frequent political and cultural references in the vocabulary of our day—that is, they are “American” psalms and they are “World” psalms. Samaras’ position and politics, in both the narrow and broader senses, drive several of the poems as the speaker responds to contemporary events and values with anger and occasional despair. Many of the poems, though—and these are the ones I’m most drawn to—are more personal lyrics that also respond to the human condition.

“The Unpronounceable Psalm,” Psalm 2 in the collection, illustrates how figurative language can be used to express frustration with the limits of language, even while exploiting the beauty of that very language. It begins with these sentences:

I couldn’t wrap my mouth around the vowel of your name.

Your name, a cave of blue wind that burrows and delves

endlessly, that rings off the walls of my drumming, lilting heart,

through the tiny pulsations of my wrists, the blood in my neck.

Many people consider that God has a name, and that God’s name is “God,” and that they can pronounce it very well. The poem here though specifies “the vowel of your name,” the breath of it linking one consonant with another. If Samaras is referring here to a specific name, it is likely the word generally translated as “Yahweh,” a breathy word itself, or he may be alluding to the fact that Hebrew is printed without vowels. Or he may not be referring to a specific name but rather to the challenge of knowing God well enough to pronounce God’s name. Regardless of Samaras’ intent, however, all of those meanings are layered into the first line. The poem continues with an explicit metaphor: “Your name, a cave of blue wind…” which extends through the sentence, until we reach its end, understanding that God’s name pulses in human veins and human blood. What is attractive to me about these lines, however, is the language and the imagery, words that invite my return until, hearing the ringing and drumming and lilting, I follow the language into its possibilities of meaning.

As this poem progresses toward its conclusion, the figurative language remains prominent, until in the penultimate sentence circles back to the imagery above:

…my words

are only the echo of you that rings within my soul, my soul

a cave of blue wind that houses the draft of you,

the eternal vowel of you I can’t wrap my mouth around.

God’s name is equivalent here to the human soul, each metaphorized as “a cave of blue wind.” and it is God, rather than the name of God, that is the “eternal vowel” here. Extending these figurative equivalencies, God is God’s name, and God’s name is the human soul, and so therefore God is the human soul. We want to be careful to avoid overinterpreting metaphor, but the theology of this poem is undeniably complex. The poem is not a treatise, however, and the reader’s primary task is not to untangle its logic. Rather, the reader surrenders to immersion in metaphor and image, the true pleasure of this text, and then perhaps considers the theology, patiently, curiously.

Some of the poems in this collection are overtly political. Others border on the mystical, though in contrast to some mystical writing, they are not impenetrable or hermetic. As with other types of writing, the mystical and the political form separate threads in this volume. Most readers, certainly those with a Christian background, will find all of the poems accessible. And like the Biblical psalms, American Psalm, World Psalm is most fruitfully read in small sections, a poem or two at a time, over the course of weeks rather than hours.