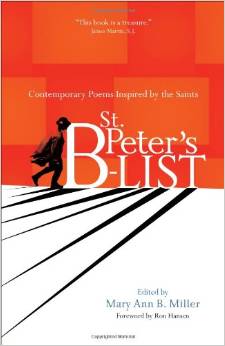

Mary Ann B. Miller, ed. St. Peter’s B-List: Contemporary Poems Inspired by the Saints. Ave Maria Press, 2014. 261 pgs. $15.95.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

I particularly enjoy anthologies that are conceived because of the editor’s interest in a topic, so when I saw a reference to St. Peter’s B-List before it was submitted to me for review, I was intrigued—for there are so many saints to choose from after all, and so many potential attitudes to express. It is one of those anthologies that’s just fun to pick up and browse through. Contributors include the well-known (e.g. Kate Daniels, James Tate, Jim Daniels, Dana Gioia) and poets who were new to me, though looking at their contributors’ notes, I wonder how I could have missed them until now. That’s a virtue of anthologies, of course, how they introduce us to poets we’ll come to love. There’s an equal range among the saints considered, from beloved St. Francis of Assisi, his companion St. Clare of Assisi, his contemporary St. Dominic, to the equally if differently beloved St. Patrick and St. Nicholas, from the Biblical St. Mary Magdalene and St. Joseph to the legendary St. Christopher, from the recently canonized St. Kateri Tekakwitha to the not-yet canonized Dorothy Day, from the famous St. Joan of Arc to the obscure St. Magnus of Füssen and St. Spyridon. Lest the obscurity of some of the saints intimidate readers, Mary Ann B. Miller has provided a helpful summary of each saint’s life, in addition to an introduction and contributor bios. The anthology is arranged in three sections, “Family and Friends,” Faith and Worship,” and “Sickness and Death.” Although many of the poems are interesting and memorable, I’ll limit my discussion here to one poem from each section.

The book opens with a Credo poem by Martha Silano, “Poor Banished Children of Eve.” It begins conventionally enough, “I believe,” and then develops through loose allusion to the Apostle’s and Nicene Creeds, though its content quickly becomes, shall we say, unorthodox. Yet it is also highly reverent, spoken in the voice of someone who recognizes a blessing when she receives one. The poem is written in tercets without punctuation, and Silano exploits this form to surprise the reader, to create layers of meaning through the juxtaposition of anticipation against the unexpected. Here’s something of what I mean—the poem begins with this stanza: “I believe in the dish in the sink / not bickering about the dish in the sink / though I believe the creator.” Unlike any canonical Christian creed, this poem focuses immediately upon the concrete material world, as if to suggest that she remains unconvinced of an abstract, invisible, ineffable world. Yet she immediately mentions a “creator,” admittedly lowercase, but perhaps the missing capital letter corresponds to the absent punctuation. But no—the sentence is interrupted with a stanza break, and the subordinate clause that has begun at the end of stanza one is completed in stanza two: “though I believe the creator // of the mess in the living room / cleans up the mess in the living room.” The poem continues this way, mentioning purgatory and hell, father and son, martyrs and saints, glory and mercy, but returning always to her immediate family, their modest inconveniences and immense blessing. Its last two lines are nearly transcendent: “grant us eternal grant us merciful / o clement o loving o sweet.” The poem is skillful and imaginative. In gesturing toward doctrine, it becomes so much more substantive than rote recitation; it ends as the prayer of a believer, one who surpasses orthodoxy to express profound gratitude.

Not all of the poems in this book express such a convincingly present faith, but many of the most moving ones do. Nicholas Samaras’ “Apocalypse Island” is filled with humor and hope. It is a list poem, structured in couplets, that describes a day from the speaker’s youth. Each of the first six couplets contains the clause “I remember” or a close synonym followed by a concrete image—though only the first two couplets actually begin with these repeated words. Samaras introduces enough variety in the length and structure of his sentences so that the repetition of “I remember” becomes resonant rather than monotonous. Then, exactly mid-way through the poem, we come to two couplets that interrupt the pattern: “Halfway up the mountain path, we came to a sign / nailed to an olive tree, a white sign in the rough // shape of an arrow, inscribing ‘this way to the Apocalypse.’ And my stunned translation, hysterical with laughter.” Five more couplets follow, two of which include “I remember.” The pacing of this poem is masterful, as is Samaras’ superimposition of his own individual future upon that revealed by St. John and the simplicity of what follows: “I remember the coolness of the air as we entered // the chapel of his Cave—Saint John of the Revelation. / All of my future was ahead of me. I framed // the twine of flowers around the ancient gold icon / and walked back into light, both empty and full.” The speaker’s future is presumably no long all ahead of him, yet we sense that this experience opened a future that will not close.

As might be expected, many of the poems in the final section are more somber than those earlier in the book. “Rose-Flavored Ice Cream with Tart Cherries” by Karen Kovacik, for example, is poignant and wistful. The poem begins evocatively, “The June air’s woozy with unshed rain,” and develops through concrete imagery, addressing a “you” by the end of the first stanza, a “you” whose favorite saint was Thomas, the doubter, or as the speaker says, “your favorite saint, who had / to touch the wound of light to believe.” The speaker orders the ice cream of the title, so exotic as to seem almost impossible, “crisp as a chilled corsage, / fragrant then tart.” Only with the subsequent line are we certain the addressee is absent, and only in the third and final stanza do we realize why—the speaker is a widow, recalling the attentive erotic care of her deceased spouse. The poem concludes with an imagined gesture reminiscent of the first stanza: “I can almost feel, a continent away, / the flutter of your impatient hands.” It was Thomas’ hand, after all, that convinced him that Jesus was alive, just as a lover’s hands often convince us that we too are alive. Like many of the poems in this anthology, “Rose-Flavored Ice Cream with Tart Cherries” doesn’t examine the life of a saint so much as it achieves understanding of the speaker’s life through reference to the saint.

The poems in St. Peter’s B-List vary in length and form; although many are written in free verse, the anthology also includes several written in received forms. Most, however—and this is my only complaint—are stylistically similar; the personal lyric dominates the collection, perhaps through the editor’s preference or perhaps because contemporary poems incorporating references to saints are most often written in this lyrical scenic mode. If the latter is true, let it also be a challenge—what can we poets do next, exploring our relationship with the saints and their influence on us, to make it new?