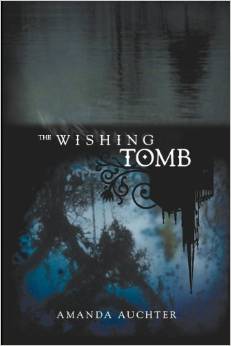

Amanda Auchter. The Wishing Tomb. Perugia Press, 2012. 87 pgs. $16.00.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Before I read a single poem, I suspected I would enjoy Amanda Auchter’s The Wishing Tomb. Simply by skimming the table of contents, I could tell that Auchter is a poet engaged with language, its specificity, the sounds of one word colliding with another. Here are some of the poems’ titles: “The Good Friday Fire,” “The Punishment Collar,” “Testimony of Evangeline the Oyster Girl, 1948,” “The Angola Inmate Coffin Factory,” “The Chicken Man Walks the Quarter.” These are not generic titles, the last resorts of a poet desperate for anything more creative than “untitled.” And fortunately, the poems are as interesting as their titles.

Like some other recently published collections (Lesley Wheeler’s Heterotopia and Nicole Cooley’s Breach spring immediately to mind), The Wishing Tomb focuses on a particular city, documenting in this case the history of New Orleans. It is divided into three sections, the first beginning with early European contact and proceeding through the nineteenth century, the second exploring events of the twentieth century, and the third tracing the effects of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill. The book is not, however, simply a history text broken into lines. The poems imagine the perspectives of specific characters, some famous, some anonymous, and the effects of catastrophic events on ordinary people. Not surprisingly given its location, the books overflows with water as a literal and metaphorical presence. Images and figures of speech echo each other from poem to poem, enhancing the collection’s unity, yet the writing is taut and requires an attentive reader. Individual poems also connect with each other to weave each section together, “The Good Friday Fire” and “The Good Friday Flood, 1927,” for example, or “Early Pastoral” which is the second poem in the collection, “Highway Pastoral” which is nearly centered, and “Late Pastoral” which is the final poem in the collection. As a book, The Wishing Tomb is as thoughtfully constructed as the individual poems.

“The Disordered Body” from section one illustrates several of Auchter’s strategies. It opens with a set of images that appeal to multiple senses: “Rain falls from the black skies daily, the city // a shroud of rot: garbage and heat and humidity, / the bright stink // of bodies. The body a branch after lightning, a language // of fever, delirium…” In the first line, the rain is comparatively neutral, even if the “black skies” are not, but by the second line, readers feel the weight of humidity and stench. The repulsion of the olfactory image extends into the next line, but then line four turns in a new direction, creating a visual image and metaphor that is almost mystical: “the body a branch after lightning, a language…” Eventually, with the mention of mosquitoes and suggestion of impending disaster, readers understand that this is a poem about yellow fever and the inevitability of nature’s power despite human intervention. The poem concludes with these lines: “We do not / say it will not come. It will come. // It will bring its terrible song, hum it into our houses.” The penultimate line is effectively emphatic, with the simple sentence “It will come” concluding both the line and the stanza, without however calling undue attention to itself as it would if it had formed a line by itself. This line consists of eight monosyllabic words, and arguably up to six stresses, further emphasizing the inevitability of the fever. Then the last line, a stanza of its own, slows the rhythm down, becoming almost melodic—“It will bring its terrible song, hum it into our houses”—through the softer sounds, the number of unstressed syllables, the alliteration. This last line is equally ominous yet also oddly beautiful, an effect created through both image and rhythm.

“The Disordered Body” gains significance from its position, immediately following another poem that describes yellow fever, “American Plague,” and preceding one that describes rituals of grief, “Mourning Brooch and Earrings, c. 1866.” This latter poem also begins with a reference to the body and concludes with an image of a person who “hums and threads, hums // and threads.” The humming here is different enough from the mosquito’s hum in “The Disordered Body,” however, so that the imagery remains fresh, echoing the language from other poems without defaulting to a poet’s linguistic tic.

Bodies and body parts—mouths, hair, tongues, hands—populate many of these poems, less to evoke eroticism than as signifiers of pain and loss. These are bodies that suffer and die and then are mourned through voices emerging from other bodies. Yet the book is ultimately as much about hope and longing as it is about pain and suffering. The final poem, “Late Pastoral,” describes an oil spill and its clean-up. Mourning a lost romanticized past, it opens with these lines: “How beautiful this was in the beginning: / white mulberry, Indian corn, a source // without suffering, without crime.” The speaker describes oil-covered birds, sand, fish. Then the conclusion recalls the opening lines: “How beautiful this was when the sun flickered / silver in its earnest rising. How much we want / to unstrangle the marshes, the oil-rolled shoreline, to return // to the light in the cypress, the mangrove, oxgrass. The stirring / of seabirds rising, rising.” As much as we long to return to an unspoiled paradise, we are unlikely ever to realize that dream. Yet the poem ends with ascent; sometimes individuals and even species recover.

The Wishing Tomb is Amanda Auchter’s second collection. (Her first, The Glass Crib, was published in 2011.) I hope we’ll have the opportunity to read many more.