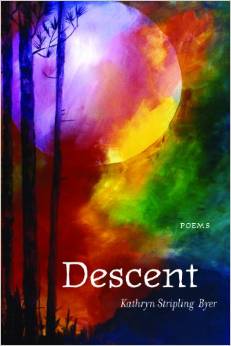

Kathryn Stripling Byer. Descent. Louisiana State University Press, 2012. 57 pages. $17.95.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Descent, Kathryn Stripling Byer’s sixth collection of poetry (her first, The Girl in the Midst of the Harvest has also recently been reprinted by Press 53), is arranged into three sections, each exploring a different aspect of biological and cultural descent. Part I explores the lives and deaths of Byer’s ancestors, particularly her grandparents. Part II focuses on southern culture, including of course questions of race and privilege. Part III returns to more immediate, apparently autobiographical, experience, though these poems also situate themselves within the context of family.

Byer demonstrates facility with a range of forms in this collection, from free verse to sonnet sequences—many of the poems, in fact, whether in free verse or received form, are arranged as sequences. Byer seems unusually engaged with and adept at the demands of poems organized as a series or divided into sections, a strategy I appreciate. Such poems permit a poet to examine a subject from multiple perspectives, to return and return to an obsession without repeating herself.

Among my favorites is “Drought Days,” a long poem in nine sections centered in Part I. This poem explores several of the book’s central thematic concerns—belief and disbelief, what we see when we see ourselves, quotidian demonstrations of care for another, the significance of landscape. It is dedicated to the poet’s grandmother, and it examines her character and personality in a time of drought. “Rain, because prayed for,” the poem begins, “was always called God’s answer, / God being what gave / or withheld whatever we needed.” Everything comes from God, in other words, even when it doesn’t come. This opening stanza suggests the circular reasoning that almost inevitably forms a part of belief—expressing a prayer defines its fulfillment as an intentional answer in a way that expressing a wish, for example, does not. When rain follows a prayer for rain, the prayer has been answered by God. When rain follows a wish for rain, however, the wish has been fulfilled, but by whom? The speaker rebels against a God who withholds, the judgmental God whose judgments are inexplicable, and she describes her rebellion with a particularly memorable image: “God stank like a singed field.” Who would worship such a creature? Certainly not the speaker. Her grandmother does, but her grandmother would presumably describe God with different imagery. She looks out her window and sees “corn that sang when / the wind came, a husband who shoveled hay / into the cow pen, the empty yard waiting // for the child growing inside her…” “Drought Days” presents the grandmother as a woman who has both a simple life and high standards for it; the poem also develops an implied narrative as the speaker grows from a girl to a woman. In the last section, the speaker is a girl again, playing with cousins as they try to compensate for a dried-up pond. They fill an oil drum with water, pretend they’ve gone to the beach. But the “water began to smell / rusty, more tractor oil to it / than tropical coconut.” This image encapsulates the children’s identities: “We would always be / hicks. Pink and flabby like pickled / pig flesh in our grandmother’s jars.” To be persuasive, fantasy paradoxically requires some basis in reality, and tractor oil is simply too distinct from suntan lotion. Its aroma is too pervasive a reminder of their distance from the sea. The section ends with a reflection on “Soul food,” and stories that belong to others, returning the poem to its beginning. Although the speaker no longer seems to be actively rejecting her grandmother’s version of God, she nevertheless remains as excluded from the community of believers as she is from the social class of those who vacation on Myrtle Beach.

The figurative language in this poem works particularly well, as do other choices Byer makes. The lines breaks, for example, in one of the stanzas quoted above exploit the reader’s anticipation and then emphasize the children’s disappointment in their situation. Here is the full first line of the seventh stanza: “on the farm. We would always be”; the enjambment at the end could be read to encapsulate hope, but the full line, read as a line rather than parts of two sentences, undercuts that optimism, for there is no hope for change. The pessimism is confirmed with the beginning of the next line: “hicks.” Byer exploits this primary difference between poetry and prose to create layers of meaning that the sentence as simply a sentence—“We would always be hicks”—could not sustain. This final section of “Drought Days” contains 27 lines, 20 of which are enjambed. None of the line breaks calls undue attention to itself, yet they all contribute to the poem’s resonant effects. “Drought Days” is the work of a poet who understands how control of craft can significantly contribute to development of theme.

Descent contains several poems that expand the poet’s vision into a broader social realm, particularly the six-part sonnet sequence “Southern Fictions” in Part II. For me, however, the most memorable poems are those that explore the speaker’s relationships with her direct ancestors. These more personal poems remain interesting because the speaker herself seems not quite resolved on their meaning. There’s always more to be understood by the speaker—and so there’s also always more to be understood by the reader. These poems are effective because they can be known, but never completely.