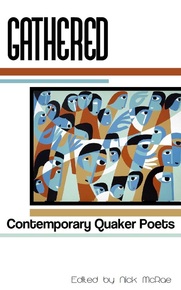

Nick McRae, ed. Gathered: Contemporary Quaker Poets. Sundress Publications, 2013. 164 pgs. $16.00

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

I’m a collector of anthologies, not so much the conventional ones organized by nation and period and intended as textbooks for literature courses, but the quirkier sort, those that illustrate an editor’s obsessions, often gathering poems according to their subject matter or form. On my shelves now, I see anthologies devoted to poems about science and mathematics, poems responding to the paintings of Edward Hopper, poems reinterpreting classical myths. I see an entire book of ghazals; one of my own poems is forthcoming in a collection of sestinas. Several of the anthologies I own focus on religion, spirituality, the Bible—for such are my own obsessions. So it is no surprise that Gathered: Contemporary Quaker Poets, edited by Nick McRae, has found its way into my hands. (Full disclosure: I am not a Quaker, though I am a student at the Earlham School of Religion, where I have taken a couple of courses in its Ministry of Writing.) McRae has done an admirable job collecting work by poets whose worldviews—and, often, aesthetic practices—overlap without defaulting to monotony. The poets may assume a similar frame of reference, in other words, but they gaze out into the world from different angles, settling their vision on their own individual landscapes.

The work of a few of the contributors—David Ray, Sarah Sarai, Maria Melendez—was familiar to me, but many writers were new. Several of the newer poets have not yet published books, but their work is widely available in literary periodicals. Many of the poems overtly address religious themes, while others consider ethical challenges—of war, hunger, environmentalism. Yet others explore those universal subjects of love and loss, birth and death; these poems both gain significance from their context and contribute to the collection’s significance. Familiarity with Quakerism will deepen a reader’s understanding of some of these poems, including several that rely on light or silence as controlling images and one written in the voice of early American Quaker John Woolman, but none of the poems will be too obscure for someone unfamiliar with this spiritual tradition.

As occurs with most reviews of anthologies (or of any book, really), I’ve marked many more poems than I have space to discuss here. So I’ll focus on only two, “[Because it is perishable]” by Jennifer Luebbers and “Mrs. Noah Breathes with the Animals” by Elizabeth Schultz. These two poems are dramatically different in form, yet they have each managed to stay with me. “[Because it is perishable]” is written in short couplets with the second line consistently indented. The entire poem consists of one long sentence. As striking as the syntactical control, however, are the sonic effects. Internal rhyme, off rhyme, alliteration, and assonance mark the poem, intriguing the ear, but subtly. The poem begins this way, with the title functioning as a first line:

[Because it is perishable,]

the day, with its vinegar &

orange, its coffee gone

cold & porridgesolid on the sill…

My eye is attracted to the spacing, and then my ear perks up at “orange…porridge.” The imagery isn’t necessarily pleasant, but it is peculiar enough to arouse my curiosity. After describing a fantasy of a day, the speaker acknowledges that what

we really want is someone

to witness each day:our names for each other,

our words for things—always, friend, I will hear

your voicesinging in the sound

of paper.

The friend’s voice is singing, therefore, in the materiality of the poem, even as the words are literally spoken by the speaker (even though no one, of course, literally speaks on paper—and even as here, we read pixels on a screen rather than ink on paper). Most of us do want someone to witness to our days, our lives, to testify to them, and isn’t that what poetry does, partly—bear testimony to the notion that we have lived.

One of the attractions of many anthologies is stylistic variety. Compared to “[Because it is perishable],” Elizabeth Schultz’ “Mrs. Noah Breathes with the Animals” looks much more conventional on the page—every line is justified left, each of the two stanzas fourteen lines long. The form doesn’t force a reader to pause, wondering at the juxtaposed imagery, and yet I did pause, considering the voice, its insights, the speaker’s situation. When I think about Noah’s ark, I’m grateful I wasn’t on it, mostly because I imagine the stench of all those cooped up animals. In this poem, however, Mrs. Noah expresses a more generalized weariness: “I was exhausted / by miracles,” she begins. She feeds the animals, many of them carnivores—this isn’t yet the peaceable kingdom after all. Her aim seems only to get through the day, apparently too tired to wonder whether this experience will conclude on dry land. They have lost track of sabbath, and she finds no rest, though as the poem ends she does notice one gesture that might, possibly, offer spiritual sustenance: “Perhaps the kangaroo, dainty / hands lifted to her face, prayed. / There were no answers, only / the surge of our breathing.” The prayers aren’t answered unless breath itself is the answer. Some days, breath is enough to pray for.

I did find a few of the poems less interesting, too dependent on modifiers or too ordinary in their language. Such is the nature of anthologies. Reading them, I inevitably ponder the selections, considering the extent to which my own choices would have coincided with the editor’s. But such also is the privilege of an editor, to create a collection that illustrates his own vision. The contents of Gathered demonstrate an editor’s thoughtfulness. I’ll be returning to it, rereading many of the poems, seeking out more work from these contributors.