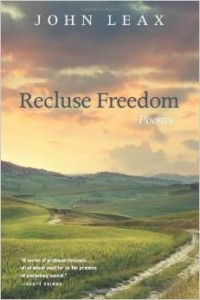

John Leax. Recluse Freedom. WordFarm. 2012. 127 pages. $18.00.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Longer than many collections of poetry, John Leax’s Recluse Freedom reads almost like an edition of selected poems. The poems are arranged into five sections which differ from each other in form or style as well as content. The first section, “Writing Home,” consists of ten narrative poems that follow the speaker’s development from boy to young man and then into the near present. Although these poems are not rigidly metrical, neither are they absolutely free verse; they demonstrate Leax’s skill with accentual patterns, for while the stressed syllables clearly resonate in the reader’s ear, there is no thump, thump, thump of the bass drum that sometimes dominates contemporary poems written in metrical forms. The second section, “Bright Wings,” contains eleven poems about birds—crows, herons, grosbeaks, a hummingbird, an owl, even vultures. Although the speaker is occasionally present via a first-person pronoun in these poems, more often the world beyond the human is central. Obviously, someone’s eye is observing the birds as they turn their necks, build their nests, take flight, but they are not reduced to containers for human insight or catalysts for human epiphany. In the third section, “Recluse: An Adirondack Idyll,” prose poems predominate, although four pantoums are interspersed among them, each pantoum consisting of four stanzas. Next, “Walking the Ridge Home” contains seven poems, or seven sections of one long poem, that are among the more formally experimental in the book. Devoid of punctuation, they depend for their rhythm—and to some extent their meaning—on line breaks, indentations, and white space. Each of these poems takes a line from the Psalms as an epigraph to guide both the writer and the reader. Finally, the last section is called “Flat Mountain Poems,” and the poems here explore that oxymoron and other paradoxes of human life. Yet Recluse Freedom is not simply five chapbooks bound within one cover. The poems are united through their attention to the natural world and through the contemplative tone. The speaker honors the world by attending to it, and by receiving it without wishing it to be other than it is.

“Homecoming,” from the first section, is one of Leax’s most thematically complicated poems. Filled with scriptural allusions, the opening stanza subverts traditional assumptions about obedience and disobedience, violence and peace, safety and harm. Here is that stanza: “In the beginning there was war, / and my father, hardly more than a boy, / was called. Because he had no church / to witness to the peaceful heart / that spoke a living word within / his chest, he went, and he became / a silent man. In the chasm / of his obedience I fell, / plunged with my first steps / into the wash of blood—a slash / of milky glass split my face from nose / to cheek and left me just one eye to watch / for his return. My mother wept, / I’m sure. No one told my father. / He soldiered on in ignorance of the night / already settling on his day.” Obviously the first phrase harkens back to Genesis, but here there is no God declaring everything good. Violence begins, not after the fall, but with creation. The speaker’s father is “called,” not by God but by the draft board. His “living word” is silenced. And then the speaker experiences his own fall, not through disobedience but through his father’s obedience. In the center of the poem, the father is present for the liberation of Dachau, and after the horror there, “No prayer / he’d learned in the bright bedtimes / of his farm-boy youth could halt the stone / rolling inexorably between the close / enclosure of his mind and the wide / goodness of the life he knew before the word / descended void in vengeance, blood, and bone.” The stone here is not the one rolled away from a tomb to indicate resurrection, and the word that descends is not the messianic promise of peace. Thirty years later, the father dies with a shrug. At his funeral, the speaker considers his father’s experience, God’s knowledge, and the overlap between them: “should / God come down to answer for this world, / he too might break his silence with a shrug, / give up, and die, helpless before the blank / enormity he’d meet in flesh.” The speaker recalls the day his father came home from the war, when they would meet for the first time: “Each time a man, young, joyful, in uniform, / descended from a bus, I cried, / ‘Is that him? Is that him?’ / I can’t remember when she said, ‘Yes,’ / or if he took me in his arms / and touched my face with his.” He remembers the longing but not its fulfillment. The poem suggests that God remains aware of this world but also remains entirely absent from it, or, at best, powerless within it. Yet the speaker acknowledges that he might not recognize God if they did meet face to face. This poem is less angry than resigned. It is a poem of faith despite the evidence that should negate faith.

“Homecoming” is not particularly typical of Recluse Freedom—none of the poems in this collection is particularly typical of it. Yet each of them is interesting, and together they form a collection that testifies to the breadth of Leax’s skill, the variety of his practice. It is a book that should be read slowly, over a period of days, because the individual poems invite contemplation. It is a book that offers us a pause from our worldly concerns yet ultimately recalls us to the world.

——————————

To submit a guest review or a book for review consideration, fill out the contact link.