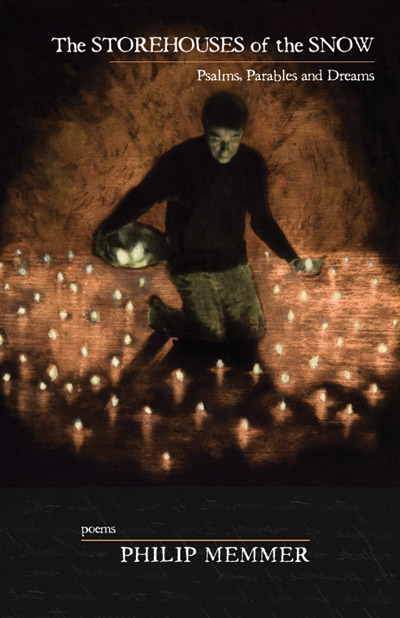

Philip Memmer. The Storehouses of Snow: Psalms, Parables and Dreams. Lost Horse Press. 2012. 67 pgs. $15.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

We’re fine with dreams, most of us, but who will say what a psalm is, or what a parable does? Psalms in the Bible, of course, address God and are often attributed to King David; sometimes they curse enemies, and sometimes they praise creation. Sometimes the speaker moans about his sorry state before cursing enemies or praising creation. Parables seem to be straightforward enough, once we’ve read Jesus’ explanation—but then sometimes we take another look and say hey, wait a minute. There are other interpretations too. Parables are slippery creatures, never quite securely within our grasp. And along with its psalms and parables, the Bible is full of dreams, though not the kind of dreams we describe today. Biblical dreams are never silly; they’re often seeking an interpreter; they’re always prophetic. So what is Philip Memmer doing in his fourth collection, The Storehouses of Snow, whose contents consist entirely of pieces labeled “dream,” “psalm,” or “parable”?

When I read Memmer’s Lucifer: A Hagiography a few years ago, I was astonished. He’d taken a character I thought I knew well enough and revised him sympathetically. Although he provocatively called that book a hagiography, it also reads like an extended parable, for it is a story we want to keep turning over in our minds, understanding more and differently each time. The Storehouses of Snow is equally rewarding, though structured very differently. It begins with a piece called “Psalm” that functions as a preface, then contains eight sections, each consisting of three parts, a “Psalm,” a “Dream,” and a “Parable,” not always in the same order. Between sections four and five, he places another single “Psalm,” and the collection concludes with another “Psalm.” Each of these pieces takes our conventional notions of the form and adapts it to a 21st century psyche, inevitably informed by at least as much skepticism as belief.

The opening psalm challenges us to consider the relationship between ourselves and our belief—perhaps the two words, “self” and “belief,” are after all just synonyms; perhaps the symbol that links them is just an equal sign. Or perhaps it’s desire that corresponds to belief, and meaning is simply projected desire. This psalm consists of three short stanzas (every poem in the book relies on this pattern of tercets, an opening line followed by two indented lines). I’ll quote the second two stanzas: “I can tell myself I see you, / until I realize / that I face you // with both eyes shut, and the dazzle / I might have called truth is / my own bright blood.” As a preface, this poem seems to warn us not to put too much faith in, well, faith. Such would seem to be the end of it, if the entire book that follows didn’t also address this “you.”

Many of the psalms here invite consideration, discussion, pondering. They include memorable lines: “Because you are always ceasing / to be, and then ceasing / to cease to be” and “How, Lord, could you have created / a creature such as me, / enamored with // (of all the things here in this world) / the freshness of a field / of new asphalt?” and “looking down / through December // to this one mystery floating / so cheerfully towards / its own melting…,” this last from the title poem. Their language both replicates Biblical language and reads as entirely contemporary.

The poems that intrigue me most, however, are the parables. They captivate as riddles do, each solution a surprise. In one, a row of houses is broken into by thieves. The parable begins with a generalized situation, as parables are prone to do: “There was a street.” The first two thieves do what we expect thieves to do—they break windows and locks, hunting for valuables. But they leave empty handed because they find nothing of interest. The third thief, however, walks in through an open door and claims the house as his own. And then, the poem concludes, “like this man—and though / you will always // be a thief in your heart—you must / find the kingdom empty, / then make it yours.” Perhaps this parable reflects the opening psalm, in which we see only our own blood but call it glorious. Even so, this parable suggests that we can make a kingdom of emptiness. The poem is as successful as it is because the final turn, beginning in the penultimate stanza, transforms it from a simple story to an invitation to perceive ourselves anew, with understanding and compassion. In the final parable in the book, three voices sit before a teller, each voice hoping for favor. They are Lie, Truth, and Story. The teller lies on his deathbed, and distinctions among the three voices fade. After the teller does die, the three share his heart: “for the last time, / in their terrible greed, / they devoured it.” But before this moment, when the three notice that the teller has died, they interpret the event according to their own preferences: “He’s better off, sighed Lie. / And in his sleep, // smiled Truth. Story said nothing…” But Story does say something eventually, “There once / was a man…” Story seems to have the last word, converting the teller into a story, one that resembles a parable in its opening. Is every story a parable, every last word a riddle? Perhaps. We are left to make our own kingdoms of—no, not emptiness—but language, which insists on meaning.

As for the dreams, they too are provocative. I encourage you to read the book and discover them for yourselves.

——————–

To propose a guest review or submit a book for review consideration, fill out the contact form.