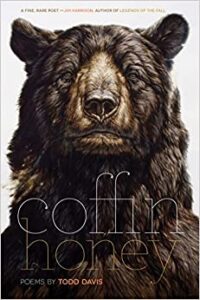

Todd Davis. Coffin Honey. Michigan State University Press, 2022. 125 pgs. $19.95.

Todd Davis. Coffin Honey. Michigan State University Press, 2022. 125 pgs. $19.95.

Coffin Honey, Todd Davis’ seventh collection, is one of the most carefully structured collections I’ve read in a long time. The individual poems address several primary topics—southernness, a boy’s sexual abuse by an uncle and the idea of the bear. These topics eventually coincide, but I won’t discuss the poems wherein this occurs because—and who would ever think this would be an issue in a collection of poetry?—I’d have to warn you of spoilers. The individual poems are memorable and attentively crafted; they not only withstand but nearly demand rereading.

Close to the beginning of the book, “Buck Day” describes a teen-age girl’s experience hunting with her father. Davis had made the risky choice (risky because the voice could so easily become condescending or didactic or simply unconvincing) to convey the events through the girl’s close 3rd-person point of view. The poem is complex, addressing the girl’s history of cutting herself, her thoughts on Biblical stories, and the comfort she derives from sitting in the deer stand with her father. Most, but not all, of the stanzas are tercets, and most often, the final line of each stanza is significantly shorter than the others. Regardless of the line length, each stanza is end-stopped with a period. As a result, each stanza concludes definitively, permitting Davis to weave several moments from the girl’s memory into the present. Here are stanzas 3-5:

She looks forward to these gray days: to sitting quietly

and saying nothing, to absorbing the cold. In the stand,

her shoulder rests against her dad. She lays the rifle, precise

as a ruler, across her lap.

During sophomore year, when she cut herself,

she used a razor in the bathtub. The water blurred red

lines, like a story with no end.

The moon’s nearly faded. Her dad nudges her.

Forty yards away a doe and spike figure-eight the field.

He whispers, “Yearlings,” says they’ll be tender.

The introduction of the “spike,” here a somewhat technical term meaning a young buck whose antlers haven’t yet developed a wealth of points, will acquire greater significance later in the poem and assist Davis in consolidating the poem’s themes. Watching the deer, the girl feels ambivalent:

She likes the taste of meat but hopes they’ll keep running.

Her dad won’t let her shoot at a moving deer.

The doe doesn’t stop, but the spike falters, halts and bends,

mouth tugging at a fern.

She squeezes the trigger.

On the felt board outside Sunday school, Jesus waits

for Roman soldiers to nail him to the cross.

Her dad smiles as they walk to the animal, says

“Now the real work,” and hands her the knife.

The “spike” evokes a specific Biblical story, the center of the New Testament of course, the crucifixion. The girl’s body, the buck’s body, the body of Jesus—all of them are cut open, all of them are marked by their shed blood. Four stanzas later, the poem ends masterfully:

She cuts away the deer’s heart, gives it to her dad,

who slides the warm meat into a plastic bag

where blood, still pooled in one of the chambers,

begins to leak out.

This poem is successful in part because of its structure. In telling one story of the events of one morning, it tells several stories. Yet several other craft decisions also contribute to the poem’s effect. The lines and sentences are deceptively straightforward, most often beginning subject-verb and developed with a variety of phrases but seldom incorporating any subordinate clauses. The vocabulary is accessible; monosyllabic words dominate. The poem is, as a result, exceptionally easy to follow. In being straightforward, however, these lines are far from flat. In the stanzas quoted above, Davis includes internal rhyme (“the spike falters, halts and bends”), and he exploits his monosyllables such that some lines and passages become nearly iambic (“She likes the taste of meat but hopes they’ll keep running”). When Davis enjambs his lines, he’s obviously attentive to the distinction between the line and the sentence, to the potential enhanced meaning of the line (“Jesus waits / for the Roman soldiers to nail him to the cross”). So although this poem can seem straightforward, it is far from simple.

Many of the poems in Coffin Honey are organized around an implicit narrative. Some of the most significant, though, are more elliptical and sometimes printed on the page in staggered lines, each often containing only a word or two. The meanings of the lines emerge more haltingly, as the sense is interrupted and disrupted by the extended space between words. This style is most notable in the multi-sectioned title poem and in a series of four other poems that seem to mark section breaks within the collection and that are each titled “dream elevator.” It is in these poems that the speaker’s sexual abuse is revealed, so their structure reinforces the nature of traumatic memory, as does their placement at irregular yet frequent points within the collection.

The range of styles and forms in Coffin Honey testifies to Davis’ depth as a poet. Although each individual poem is accomplished, it is the collection as a whole that is most impressive and sophisticated. It is timely and timeless. It is thoughtful and thought-provoking. It encourages the reader, to paraphrase the girl in “Buck Day,” to sit quietly and say nothing.