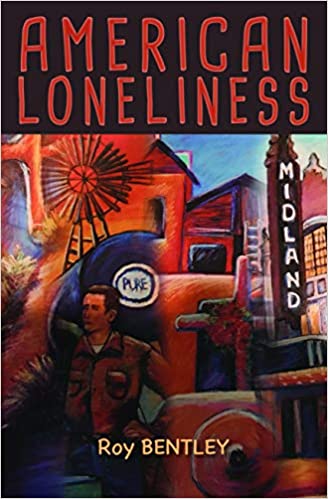

Roy Bentley. American Loneliness. Lost Horse Press, 2019. 85 pgs. $18.00

Reading Roy Bentley’s American Loneliness is exceptionally gratifying. The individual poems are ambitious, and there are many of them, 68 altogether, that take the reader on a wild jaunt through American popular culture. The poems consider the Wright brothers, the Kennedy family, James Brown, Janis Joplin, movies, television,

shipyards, factories, automobiles, astronauts, Appalachia, Ohio, and California—as well as hope and despair, right and wrong, relationships, and, as the title indicates, loneliness. They take people and their stories seriously, respecting both their subjects and their readers.

Bentley’s poems tend to fill the page—they’re long-ish poems with long lines. They look dense, but the language itself is conversational and colloquial. Their impulse is narrative, yet they also take full advantage of elements most often associated with poetry, especially concrete imagery and sonic devices like alliteration and assonance. And Bentley is also a master of the rhythm of the sentence. His long lines permit him to play the sentence against the line, his stanzas revealing meaning differently than paragraphs would but also differently than more forcefully enjambed shorter lines would.

“The Afternoon My Father Met Ted Kennedy” is among the more somber poems in the collection. It describes a plane ride and conversation mingled with alcohol, the two men share. Here is the second and final stanza:

…I’m told that the Senator from Massachusetts

smiled under the gaze of the Bond-girl flight attendant.

While they were together neither mentioned murder or

assassination, my father’s handiwork in the Korean War,

any sort of slaughter, though Kennedy finally leaned over

the audibly ticking clock to ask my father what he thought.

About this life. The world in general. And what if I say

he said, Thinking is way above my GS-11 pay grade—

which had Kennedy doing a spit-take. Spewing Scotch.

My father said Ted Kennedy laughed like he was a man

without a serious care in the world but stopped to look

for a moment out the window by his seat in First Class.

Maybe the spray called to mind blood and exit wounds.

The merriment before last breaths taken in limousines.

Through much of this stanza, information is conveyed comparatively objectively, though word-choices like “handiwork” and “slaughter” remind us that we are listening to a speaker with opinions. Near the end of the stanza, though, the information slides from observable activity into the speaker’s speculation, suggestions that implicate both men. The speaker seems to hope that both men experience reminders of the results of their decisions, but the poem offers no evidence that such is the case, and I suspect that both men have become adept at justification and denial.

The imagistic link between the spit Scotch and the “spray” of “blood and exit wounds” is one indication of Bentley’s skill. If we look at lines three and four above, we see that they nearly scan, the third line basically trochaic and the fourth iambic. The phrase “neither mentioned murder” particularly catches my ear, its regular rhythm enhanced by the alliteration and the repeated “er.” This phrase also slows the rhythm down considerably. If we insist on defining end-stopped lines as those which conclude with a punctuation mark, this stanza is nearly evenly divided between end-stopped and enjambed lines, but several of the lines that look enjambed actually do break at a grammatically logical point, e.g. “like he was a man / without a serious care…” Instead of relying on heavily enjambed lines, Bentley varies the rhythm through caesuras, “About this life. The world in general. And what if I say” or “which had Kennedy doing a spit-take. Spewing Scotch.” The length of his sentences varies more widely than the length of his lines, and the difference between the two helps him alter his rhythm.

Other poems focus on the ordinary un-famous individuals among us, “The Keno Caller at the Oxford Café in Missoula,” for example. Yet, these poems are at least as effective as those that mention Ted Kennedy or movie stars at revealing the meager hope that characterizes so many lives. In “The Keno Caller…,” the scene reminds the speaker of moments in his childhood; layered connections between the two time periods emerge throughout the poem, which concludes, despite the speaker’s isolation, with something like hope: “as if grace is the etcetera we make happen / above the roar and against great odds.” In the poem, grace emerges as the effect of looking away from an individual’s loss, looking away in order to grant the other his dignity. Yet grace is also an “etcetera,” something so trivial it isn’t even worth naming. “Etcetera” relieves the speaker of too much hope followed, according to the odds, by too much disappointment. Although several of the characters in this poem seem down-and-out, the speaker, through his tone and attention, reveals that their condition is the condition of us all.

It is this quality that is most admirable in American Loneliness. The book explores the quiet desperation that characterizes so many lives, but it meets that desperation with mercy. I’m attracted to his craft, but it’s his empathy that will keep me reading his work.