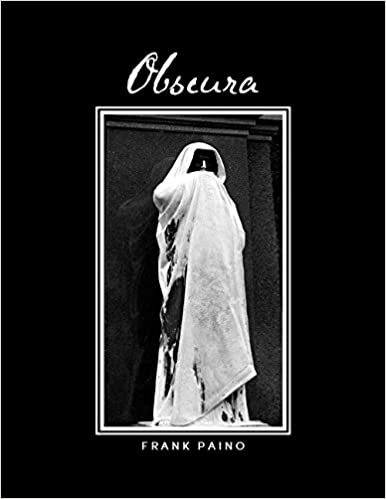

Frank Paino. Obscura. Orison Books, 2020. 81 pgs. $16.00.

Those of us familiar with Frank Paino’s earlier work have been ecstatic since the announcement that Obscura, his third collection, was forthcoming. It was certainly worth the wait. The poems in this collection are attentive and thoughtful, brimming with unusual detail but also considering what all those concrete things add up to. Their topics are the significant ones poets often attend to—

life, love, death, and whatever (if anything) follows—and they are populated by saints, devils, scientists, dogs, birds, and other creatures as they grope toward wisdom.

Among the more disturbing—and there are several that describe callous, or at least thoughtless, human behavior—poems is “Falling,” whose epigraph describes an event when a hotelier in Niagara Falls, who, hard-up for customers, sent a boat filled with live animals over the falls as a tourist attraction. Given many of the other poems in the collection, readers can’t help but also think about The Fall when they read this poem, and how truly fallen human beings are. Initially, the poem considers possibilities that might have interfered with this event:

What if the buffalo, fur matted with mud and dung,

had tucked one glass-slick horn beneath the ribs

of the man who led him aboard the decommissioned

schooner…

Or:

What if the raccoon had dragged its rabid teeth

along the pale flesh of its handler’s wrist, a surgical slice

just above the glove-line he would shrug off

until night fell with its fever and slow asphyxiation?

What if the lioness, halt in her dotage but still made

for life, had clawed a mortal gape into her captor’s jugular,

…

“What if and what if,” this section concludes—that phrase we humans tend to obsess over. None of these “what ifs” occurred, of course, for the animals did tumble frantically to their deaths. The difference between the animals’ potential harm of the humans and the humans’ actual harm of the animals is that the animals would simply have been acting according to their natures—a rabid raccoon will bite. The humans, on the other hand, offer the consent of their wills for gratuitous cruelty, a novelty to stave off ennui.

The content of this poem, developed through attention to detail, is shocking, and that shock contributes to the poem’s memorability. Its success as a poem, however, depends on much more than shock. The sounds of these lines reverberate in the reader’s ear. Take a look back at the opening, for instance. Assonance and alliteration work together, contributing to the pleasurable rhythm while remaining sufficiently subtle. The short “u” sound dominates the first lines—“buffalo,” “fur,” “mud,” “dung,” “tucked”—and mingles with the alliterative “matted with mud” and the consonance of “glass-slick,” the sibilants of that phrase suggesting both speed and menace. This stanza relies on hard sounds, in “jutting” and “scraped,” for example, and then returns to the short “u”, “thunder seemed more like / the thrum of honeybees.” Everything about this language, from the definitions of the words to the sounds they exploit, is interesting.

“Taxonomy,” one of the longest poems in the collection, also considers the place of animals within the human world, but through an empathic description of the life of Adam, who, “after a while” as each stanza begins, wearies of his duty to name:

After a while, the glitter

began to fade, the way

a bright star, regarded full-on,

becomes its own ghost

behind the shuttered eye.

After a while, he couldn’t

look past the next in line,

couldn’t bear the beastly

swizzle that curved beyond

the perfect wash of sun

that gilded the perfect pasture

in perfect shades of umber.

Paino’s use of “After a while” as an organizing device throughout this poem is oddly appropriate—for how would Adam, still inhabiting the Garden of Eden, measure time? Units of time haven’t been named, and what reason would there be for measuring time before humans were required to labor, attend to growing seasons, or experience the end of time through death? Without death, a person’s story has no end, and so no middle either, even if Adam did have something of a beginning. Even in Eden, however, Adam’s task grows tedious. Without imperfection, how can perfection be joyful, or satisfying?

Midway through, a stanza addresses Adam’s state directly:

After a while, all the whiles

congealed like blood

in a ragged wound,

and Adam named the ache

that plagued him loneliness.

He cried out from his

empty bed, felt a fist

like iron enter his side,

saw a fairer form bloom

from the snapped curve

of his floating rib.

Like him. And not.

He named this partner Eve.

Here, too, Paino is attentive to sound—“Adam,” “named,” “ache,” “plagued.” (A thorough analysis of this poem would examine all of the other Biblical references throughout, like “plagued” or the earlier “throng of lepers chasing / the hem of a dusty robe,” but a short review like this cannot accommodate such an analysis.) Paino’s description of God’s removal (without any mention of God) of his rib is particularly effective, “felt a fist / like iron enter his side.” He likely suffered quite an ache following that event, but it is the ache he named loneliness the new ache cures.

The poem ends where we might expect it to, with the banishment of Adam and Eve from Eden, but it doesn’t end how we expect it to:

…when the angel

swooped down

with his flaming sword,

they’d already taken

what little they had

and vanished,

having rolled

the thing they named freedom

across their tongues

and found it sweet.

Like spoonfuls

of milk and honey.

A land of milk and honey is what the Israelites will discover centuries later in their own experience of freedom following enslavement in Egypt. Here, though, Adam and Eve find freedom of choice, even if choice leads to misfortune, more engaging than the monotony of perfection. “Taxonomy” is itself an engaging example of how to retell a story that has been told and told again.

Obscura is accomplished and satisfying. If you’ve read Paino’s earlier work, you’ll be very glad for this new collection. If you’ve never come across Paino’s work before, start here, return to his other collections, and then wait eagerly with the rest of us for what will come next.