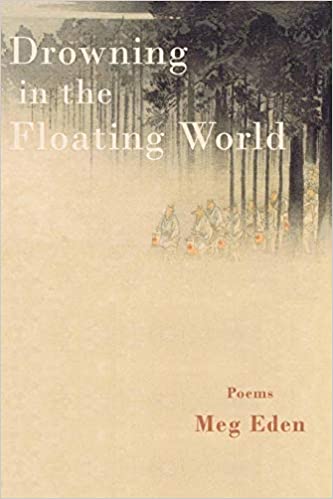

Meg Eden. Drowning in the Floating World. Press 53. 69 pages. $14.95.

The first thing readers will notice about Meg Eden’s Drowning in the Floating World is its subject matter—the earthquake of 2011 that led to the Japanese tsunami and the nuclear reactor damage that followed. The next thing most American readers will notice, I suspect, is how little they know about Japan and Japanese culture. Reading these poems attentively for content, readers will also begin to notice how adept they are with form, how their

effects emerge from skilled craft as much as content. Eden explores this disaster and her response to it through individual and communal experience. There’s much grief here, of course, but also hope—the story doesn’t end with despair.

One of the most direct narrative poems in the collection is “Corpse Washing,” designated as “after Rilke.” The speaker here is a mortician who is preparing a girl’s body for cremation in the presence of the girl’s family. Eden reveals some of the gruesome details, but she does not exploit them for shock value; the tone remains neutral, while respect for the dead requires such honesty. Toward the beginning, the speaker describes preparation of the corpse:

Her family shows me her class

picture, I compare it to

the body in front of me

bones shaped like a hand; a burrow

of dark wet flesh, overrun by maggots.

I wash what remains of her

under the funeral garb and, knowing

nothing of drowning, everything

of drowning, I imagine

the journey of her body.

I patch in the maggot holes. I fill

her mouth with cotton. The mother

brings me the lipstick she used to wear—

a bubblegum pink—and for a moment,

the girl’s lips look soft and alive.

Although some of these details are typical of funeral preparations, others are not, the maggots of course, but also the girl’s youth, the difference between the photo of the girl and her remains. These stanzas are effective in part because of their attention to concrete actions and facts, but also through the sentence structure, all of them beginning subject-verb, the most straightforward, almost journalistic, English sentence structure. The only abstract reference is the speaker’s imagining “the journey of her body,” and even that is brief, permitting readers also to do their own imagining. The last quoted line here relieves the readers from some of their horror, but that relief is momentary, as the next section begins, “I brush the seaweed and trash / from her remaining hair until it’s soft.”

The entire poem consists of eleven regular stanzas, each five lines long, the lines themselves not metrically regular but approximate enough in length to reinforce the direct presentation of detail. Only as the poem concludes does the speaker indicate how desperate this event is:

The mother takes

the last water to her daughter’s

lips, but the girl rejects it.

She’s had more than enough

water for one life.

This is how we say farewell:

the girl’s favorite dress is brought.

A summer dress, short sleeved

and red like poppies. Laid over

her body, the dress is engulfing.

Inside her coffin, the girl is lifted

to the oven. The fire is living and god-like.

She is fed into it, quickly,

before anyone can imagine her burning-alive

hair, the gnashing of that poppy dress.

Only here, at the end, does the speaker permit metaphor. The emotional restraint of the first ten stanzas heightens the effect of this final, horrifying act. The details, especially “that poppy dress,” suggest the workings of human memory, how the smallest things haunt us.

A very different poem, “All Summer I Wore,” begins with a line that could be a continuation of “Corpse Washing.” The title leads into the first line, “dead girls’ dresses.” A less imaginative poet would have continued along this line, but Eden creates an anaphoric chant, each line until the last beginning “I wore” and incorporating so much more than clothing. “I wore dresses I found on the shore, in now-empty homes,” she says in the second line, leading into the wearing of culture and cultural disaster. Other lines include “ I wore the muddy water the carried my neighbors’ bodies” and “I wore washed-up Chinese newspapers & Russian bottles” and “I wore the names of my classmates, etched in my arms.” The speaker is encased in the concrete and abstract detritus of this tsunami. The form is particularly appropriate here, its repetitive insistence reproducing in language the effect of inescapable reminders of this event.

The collection contains several poems written in received and more experimental forms—a triolet, a villanelle, a series of haiku, a prose poem. Eden handles each of these forms deftly, and her nonce forms are equally intriguing. It’s as if she wishes that this event could be understood, explained, even accepted if only she could find the right kind of language to contain it. I would discuss each of them if I thought readers would want to spend that much time reading about the poems rather than reading the poems themselves.

Instead, I’ll conclude by devoting attention to the final (and probably most hopeful) poem in the collection, “Baptism.” It describes a literal baptism of a girl named Kaylee in the ocean near Fukuoka. It opens with the pastor already in the ocean, “water dark up to his thighs.” The water this day is quiet, its blue stretching calmly to the horizon, so unlike the water that had washed over cities only a few months earlier. Then the baptism occurs:

From the shore,

we, the church, stand holding

our shoes, feet bare

in the sand, waiting. Out east,

new cities will be built.

Inside Kaylee, a renovated

city is filling.

She rises from the water.

So the collection ends, a community rising from the same water that would have destroyed it. This final poem, through its context in this collection, grants extra weight to this baptism. It is not simply a formality, nor a naïve commitment made by an individual, but a choice made by a person within a community that knows how dangerous the world can be. Still, she rises, in full view of her witnesses, as so many have hoped to rise after disaster.

I hope we won’t have to wait too long for Meg Eden’s next collection. I’m eager to hear what else she has to say, and how she will say it.