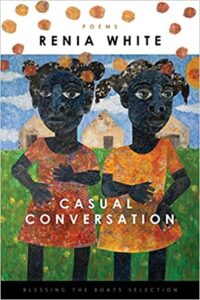

Renia White. Casual Conversation. BOA Editions, 2022. 72 pgs. $17.00.

If one element most characterizes Renia White’s first collection, it is voice. The poems in Casual Conversation are, on the one hand, conversational, but they are not, on the other hand, plain spoken or by any means flat. The voice is musical and assertive, intelligent and individualized. The poems address events that sometimes occur so frequently that conversation about them can seem casual, ordinary, common—but ought not be. Conversation about a lynching for example. Or a poem that initially seems to be about hot sauce but shifts to an exploration of race. Why do so many conversations in America need to turn to race some people ask. Because everything in America—let’s admit it—everything in America is about race.

The first poem in the collection, “hearsay,” opens with that most casual of expressions, “OK.” The speaker is responding to a companion who has revealed a bit of information, so the reader enters in medias res. The speaker provides just enough context to situate the reader, but only just enough, for the reader remains just a little off-balance:

OK so you are telling me the girl dared say

“I can’t just let you have my life,

not like that, your honor”

Occurring as it does at the end of the line and stanza, “your honor” stuns the reader—we know now that the setting is likely a courtroom, and this conversation isn’t nearly as “casual” as we might have assumed. A girl is talking back to a judge. The stakes are high. The following stanza doesn’t reveal why exactly this girl has found herself before a judge; instead, it reminds us of a much longer history and much bigger context. She isn’t standing before a judge simply because of any crime she might or might not have committed. She’s standing before a judge because she lives in a particular place that has developed through its own peculiar history:

and he sentenced her to a bedazzled tightrope

and a room without a window, and a son

that doesn’t know her name? middle passage

for this? think the girl doesn’t know her own

shame? given that face she wears? think she doesn’t

know where she is ain’t where she was put down

to begin with? that her first season was

someone else’s harvest?

In this stanza, Renia White chooses to reveal information strategically, and she exploits diction and lineation to enhance these choices. The line break following “son” is particularly effective, delaying as it does the most important detail. Then we have “middle passage” seeming to hang out on its own, as if the event it signifies were some kind of isolated event. White readers can rely on their privilege to ignore racialized trauma whenever it gets too uncomfortable or too tiring. It was a long time ago, after all, wasn’t it? The speaker insists that the past isn’t past, for “middle passage” isn’t simply a phrase tacked on to a line otherwise concerned with a single individual. “middle passage / for this?” the speaker asks. Her ancestors survived that trauma, in other words, for this? As the stanza continues, it opens up in order to position this girl’s experience within a broader context: “her first season was / someone else’s harvest?”

In its final lines, the poem challenges assumptions about privilege. Those who have it continually fail to comprehend why others don’t. That failure, of course, is a component of privilege.

some people get to want and need

and be met in it. some just the mouth

just the teeth

some eat and they say

“why all the hunger?”

This poem succeeds because it reveals just enough, challenging readers to consider their own complicity in the type of events the poem describes.

Several of the poems in Casual Conversation force readers to confront their role within these conversations. Am I part of “us” or “them”? When we say “us,” what are we ignoring about others’ experiences? “un-“ addresses these questions most directly. The third stanza reveals how pronouns like “us” camouflage difference:

this is our undoing. woman beside me in the café

says this massacre is so like us. I think of the “us”

this takes then,

she might not mean “our” us, maybe their us.

Maybe the white woman means white people when she says “us,” implicitly acknowledging racial responsibility, rather than citing a more amorphous American us that suggests the speaker and the white woman beside her aren’t all that different. The stanzas that follow interrogate but do not resolve this confusion.

but maybe we got an us too: me, her,

everyone who decides to have it.

I think that’s what she’s hoping for—distance,

something to comb out of herself through.

you know how you can undo a whole home

with the unlatching of a window? howl from the pit

beneath it? say “we did this” and “we allowed this”

and the girl beside you will forget you are white, maybe

will not query your us-ing. will not ask which “us”

of this country

The metaphor of the opened-up home—open for what? escape, to release pressure from its own looming implosion, open for burglary or looting—will dominate the final section of the poem. Meanwhile, though, White has uniquely shifted perspective, entering the mind of the speaker’s white companion: “the girl beside you will forget you are white, maybe / will not query your us-ing.” The “you” here has become the white woman, hoping the speaker will forget that she, the white woman, is white, will accept the white woman’s “us” as including them both. Again, the line break at “maybe,” allowing that adverb to modify the clause that precedes it as well as the one that follows, is crucial. “Maybe” conveys some slight hope while simultaneously undercutting it. The white woman, perhaps, wants to climb out of the open window of her white house, but she can’t quite manage it. For the house isn’t just a building, and individuals are caught up in systems that individuals can’t dismantle. The poem concludes with another question:

…still the churches burn, the window’s open,

closing it will not save us, another window won’t save us.

who is us and what are we and what do you do

with an open thing

that can’t be fixed by closing?

On its own, the question is discouraging. But the fact that it can be asked, can even be thought, is perhaps a little less discouraging.

Casual Conversation is both important and good. These poems are successful because of White’s skill with craft and mastery of voice. They are important because of their themes, their refusal to look away from the horrors of the American past or its present. This book’s literary accomplishment and cultural significance make it a necessary collection for the 21st century.