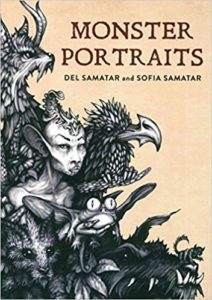

Del Samatar and Sofia Samatar. Monster Portraits. Rose Metal Press, 2018. 76 pgs. $14.95.

Del Samatar and Sofia Samatar. Monster Portraits. Rose Metal Press, 2018. 76 pgs. $14.95.

Despite anything you’ve heard about the death of this and that, we live in an exciting time for literature. Genres and styles have expanded considerably during the last half-century and particularly the last generation, with much contemporary writing challenging the idea of genre itself. The back cover of Monster Portraits, with writing by Sofia Samatar and drawings by Del Samatar, refers to the book as “fiction & art.” When I purchased this book, and as I was reading it, I read the text as poetry—prose poetry perhaps, but poetry nevertheless. Other readers would probably call the pieces flash fiction, though some sections also have the feel of nonfiction.

What difference does it make what we call a thing? Isn’t literature analogous to that rose that would smell as sweet called by any other name?

As a reader, I approach genres differently, as I suspect almost all of us do. I read poetry more slowly than prose, pausing more often, thinking less about trajectories, even though we know that collections of poetry are supposed to be arranged with an arc in mind. I’m more likely to mull over an individual word when I read poetry, and to yield my attention to other small units. Prose is made of words, too, you might say, but the units of fiction and even nonfiction are different than words—they’re paragraphs at least, or scenes. If prose is written the way masons build walls, brick by mortared brick, poetry is written the way Buddhist monks create sand paintings, grain by colored grain.

Conventionally at least.

Monster Portraits is anything but conventional, so it’s no surprise that it’s published by Rose Metal Press, which has made a name for itself publishing hybrid work. The books they publish are consistently interesting, in content as well as form. Monster Portraits in particular is puzzling and provocative, and the further I read in it, the more I liked it. Syncretic and sedimentary in their development, the pieces often rely on surprising juxtapositions that become perfectly logical by the end of the piece. Ultimately, the collection explores one question—who or what is a monster?—and also asks the more challenging one—who or what isn’t?

“The Green Lady,” for example, opens with a fantastical but direct description:

“She emerged from the sea at Rostai, crowned with foam. I had been camping on the beach. The water fragmented about her tendrilled head. I scrambled for my notebook, knocking over my little cooking pot, spilling my dinner, burning my hand on the coals.

Trembling, I scribbled her words, which blurred at once on the humid paper. ‘In our country, phosphorescence is eaten from little shells. Our castles are of coral; our herds are whales. It is the perfect place for you, except that you could not breathe.’”

The conversation between the speaker, who reveals her fear of drowning, and the Green Lady, continues for about three-fourths of the piece. Then the content seems to shift:

“In the sixteenth century, the Anabaptist theologian Balthasar Hubmaier used a play on words to attack the reverence for the sacramental wafer. In his pun, the monstrance holding the wafer became the monster that rises from the sea in Revelation 13. O monstra, monstratis nobis monstruosa monstra!” The sin was the worship of the creature in place of the Creator. The error was a passion for the image.

“The Green Lady left me retching. I’d forgotten to hold my breath.

“The monster itself is a revelation.

“Balthasar Hubmaier was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake. His wife, a stone around her neck, was drowned in the Danube.”

What does the Green Lady have to do with a Christian sacrament? Is the speaker making a theological argument? If a monster is a revelation, what does it reveal? Is Hubmaier’s wife linked to the Green Lady in any way other than through their affiliations with water?

Through this shift in content, the piece takes on significantly greater seriousness; it’s no longer simply fantasy or fairy tale (if fantasy or fairy tale are ever simply that), but also cultural commentary. Certainly, this piece is evaluating definitions of the monstrous, suggesting that the perpetrators of torture rather than their victims are the monsters. It also, however, provokes us to think about language, how relations among words sometimes signify hidden realities, how text is itself an image—and in this book, is also surrounded by actual images. Those of us who value art do often share “a passion for the image.” Perhaps all artists must at least risk heresy if our work is to be any good, not against religious doctrine per se but against received beliefs about what art can and should be.

The last piece in the book, “Self-Portrait,” confirms what we’ve suspected all along, that the distinction between monsters and other beings is neither clear nor certain nor absolute. The speaker travels through several imaginary places, briefly describing her activities in each. Toward the end, she refers to Cixous and the particular love siblings sometimes share and then addresses the reader directly:

“Here at the end I’m reduced to begging you: Endure the scar. Let an insight come and find you. The monster, in this case, would have been, emerging from a certain order of the figures, a ‘philosophy of love.’

“Endure the scar. When you’re alone, on the bus, on the tracks, in the vacant lot, on the edge of the bathroom sink, that’s where they find you.

“We went into the field to study monsters and they found us and they found us and they found us and they found us.”

This book is unlike anything else I’ve read. Like the monsters inside it, Monster Portraits found me and found me and continues to find me.