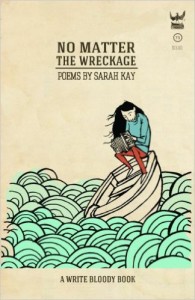

Sarah Kay. No Matter the Wreckage. Write Bloody Publishing, 2014. 143 pgs. $15.00.

Sarah Kay. No Matter the Wreckage. Write Bloody Publishing, 2014. 143 pgs. $15.00.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Sarah Kay’s No Matter the Wreckage is the print version of her spoken word poetry. (If you’ve never heard one of her performances, there are many links here.) The turn to print initially seemed odd to me since so much of the energy of spoken word poetry often emerges from its “spoken” qualifier. I wondered how this energy would emerge from the page, or if it could. I also wondered how the poetry would stand up to a silent reading pace, which is often more contemplative than the listening pace. Reading through this collection, I sensed Kay’s spoken voice fairly often, almost like an echo, more individualized than the “voice” we often speak of in a writer’s work. I was also relieved to notice that the flatter language oral communication can sometimes get away with occurs only rarely here. All this is to say that No Matter the Wreckage rewards reading as well as hearing.

Many of Kay’s poems directly address contemporary national or international events. One of the most moving, “Shosholoza,” narrates an event resulting from South African apartheid. “Hiroshima” describes destruction, yes, but also impossible survival and regeneration. Others are more personal. “Something We Don’t Talk About, Part I” describes family disintegration. In “The Call,” the speaker imagines two different possible scenarios following a call to her ex-boyfriend.

“Forest Fires” considers an environmental emergency but focuses most on the speaker’s extended family situation as it explores how individuals grieve and what they grieve for. The poem opens by contrasting a trip to California with her family’s situation in New York:

I arrive home from JFK in the rosy hours

to find a new 5-in-1 egg slicer and dicer

on our dining room table.

This is how my father deals with grief.

Three days ago, I was in the Santa Cruz

Redwoods tracing a mountain road

in the back of a pickup truck, watching

clouds unravel into spider webs.

Two days from now, there will be

forest fires, so thick, they will have to

evacuate Santa Cruz…

The first line seems optimistic with its “rosy hours,” the color recalling the fire in the poem’s title. The tone turns slightly comic in the second line, the “5-in-1 egg slicer and dicer” satirizing commercial language. Following these two lines, readers may think they know where this poem is going, how it may descend from Frank O’Hara with its brand names and references to popular culture. But then the final line of the first stanza shifts its tone, making a direct statement devoid of image or figurative language: “This is how my father deals with grief.” In the next stanza, the poem moves to the recent past, and its method returns to image and metaphor as the speaker is “tracing a mountain road” and “clouds unravel into spider webs.” Then the poem turns toward the near future. The poem moves through these time periods, juxtaposing different events according to their place in time until the fire that erupts in the future becomes a metaphor for the dying that is happening in the present. A fire burns out of control in California, while in New York the speaker’s father stirs egg salad and the speaker’s grandmother lies in a hospital bed, appreciating her family even as she forgets who they are.

A couple of stanzas toward the end of the poem illustrate how adept Kay can be with lineation. The poem is composed in quatrains with lines of comparatively similar length. The relationship of the line to the sentence is what most interests me because of how the literal meaning of the sentence can be augmented by the suggestive meaning of the line. Here are four and a half lines that demonstrate how Kay takes advantage of possibilities:

when he says no. I will leave him to slice

and dice the things he can. My grandmother

folds her hands on mine and strokes

my knuckles like they are a wild animal she is

trying to tame.

Because of the arrangement of these lines, the grandmother is affiliated with the things the father can control, or at least manage, even though the family’s inability to ward off death forms the thematic center of the poem. Similarly, breaking the fourth line between “she is” and “trying to tame” suggests that the grandmother herself is wild, at least for the split second before we read the sentence’s final phrase. Although lineation certainly affects the rhythm of a poem, whether read aloud or silently, its effects are much more dominant in print.

Occasionally, Kay’s lines do simply reproduce the grammatical unit, as in the opening stanza of “Peacocks”:

Lately? Lately I’ve been living with spiders.

But as roommates go, they haven’t been too bad.

The one in the bathroom keeps to his side of the tile,

and the one in the bedroom can get a little bit grabby,

but for the most part he keeps his hands to himself.

Most of the lines in the poem are end-stopped in this way, and both the rhythm and the language here is flatter than in “Forest Fires.” “Peacocks” is an example of a poem that benefits most significantly from performance. As I discussed above, Kay does most often exploit the characteristics of print that help distinguish poetry from prose. When her poems lose some of their energy on the page, it is often because the line isn’t constructed as attentively as it might have been. Such a comment should not deter readers from this book though. Its virtues far outweigh this one shortcoming.

I’ve both enjoyed reading No Matter the Wreckage and learned from it. The elements of craft that performance poets develop most fully and that are fully present here, especially those related to voice and style, are particularly worth mulling over for those of us who compose primarily for print. I will be returning to Kay’s work as a model for conveying energy to the page.