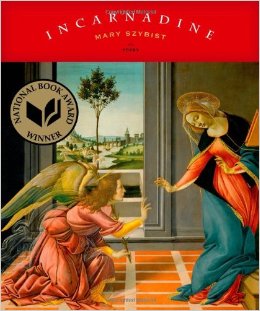

Mary Szybist. Incarnadine. Graywolf, 2013. 70 pgs. $15.00

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

Late in 2013, I asked a group of friends about their favorite collections of poetry published during that year. Several mentioned Mary Szybist’s Incarnadine. Perhaps it was fate or destiny or maybe just coincidence, but the next time I wandered into a small bookstore that generally stocks very little contemporary poetry, I saw Incarnadine on the shelf. I picked it up and quickly understood why so many readers had found it so compelling, and why it won the National Book Award in Poetry for 2013. This book explores the Annunciation, when the angel Gabriel appeared to Mary to suggest that she would become the mother of Jesus, from multiple angles and through numerous forms. Szybist’s skill with poetic craft permits her to construct a collection that is wildly imaginative. She links this story to historic persons from medieval Cathars to Kenneth Starr and George W. Bush; she retells it by listening to girls complete a jigsaw puzzle and by diagramming a sentence. She examines canonical artistic renditions, and she contributes her own words to a mural at the Pennsylvania College of Arts & Design. She doesn’t, in other words, simply repeat, repeat, repeat, or even revise, revise, revise; she exploits her obsession in order to make it new in each poem.

The collection opens with “The Troubadours Etc.,” a poem that situates us clearly in our postmodern 21st century, when we so often default to irony, deflecting belief (whether religious or not) rather than engaging with it. The poem begins:

Just for this evening, let’s not mock them.

Not their curtsies or cross-garters

or ever-recurring pepper trees in their gardens

promising, promising.

At least they had ideas about love.

Of course troubadours are easy to mock, with their stylized gestures, their flamboyant clothing, their apparent willingness to sacrifice so much comfort for romance. Yet the speaker and her companion are also traveling, following a highway west toward some unstated destination. Their setting includes pastoral details—cornfields, cows, sheep—but they are undercut by images of mechanized modernity. The cows, for example, are “poking their heads / through metal contraptions to eat,” and the sheep are surrounded by “huge wooden spools in the fields” and “telephone wires.” The speaker eventually reveals her own longing:

The Puritans thought that we are granted the ability to love

only through miracle,

but the troubadours knew how to burn themselves through,

how to make themselves shrines to their own longing.

The spectacular was never behind them.

The spectacular, in other words, was before them. They moved toward it. Yet that time is over, or perhaps only seems so:

At what point is something gone completely?

The last of the sunlight is disappearing

even as it swells—

Just for this evening, won’t you put me before you

until I’m far enough away you can

believe in me?

Then try, try to come closer—

my wonderful and less than.

At its conclusion, the poem urges a return to something like the troubadour’s belief in what lies ahead rather than only behind. This poem instructs us how to read the collection, taking an idea seriously, acknowledging our place in history and tradition. For what is a poet if not a troubadour, even one who discounts the identification by attaching “Etc.” to her title? And what is a troubadour but someone devoted to the beloved’s absence? Yet the collection is more than a troubadour’s love lyrics, for it acknowledges that while the Annunciation is a love story, it’s a story of many other things also—power, fear, violence, embodiment.

Yet tradition needn’t be solemn or even serious. “Update on Mary” is a tongue-in-cheek prose poem that quickly suggests an identification between Mary Szybist and Mary the mother of Jesus. Its opening sentence suggests that good intentions might not have changed much in 2000 years: “Mary always thinks that as soon as she gets a few more things done and finishes the dishes, she will open herself to God.” This Mary worries about her wardrobe, seeks order, enjoys cookies perhaps a tad too much. In another collection, the link between the two Marys—author and subject—might be less prominent, but here we’re virtually required to superimpose one woman upon the other as we continue reading. Then the fifth sentence states, “When people say ‘Mary,’ Mary still thinks Holy Virgin! Holy Heavenly Mother! But Mary knows she is not any of those things.” On the one hand, Mary Szybist could easily experience these thoughts; on the other hand, Mary the mother of Jesus could also be critiquing historic interpretations of her. This poem is among the most humorous in the collection, and the humor is refreshing, urging us not to take ourselves too seriously or our faith too solemnly.

I don’t want to spend so much time discussing the content and themes of Incarnadine that I neglect Szybist’s accomplishments with craft. The book includes poems in free verse and in form, including forms Szybist has created. But she occasionally also adapts received form, writing poems that allude to received forms without actually representing them. For example, the form of “I Send News: She Has Survived the Tumor after All” alludes to the villanelle through its rhyme scheme and tercets, with a concluding quatrain, but it does not include the salient feature of a villanelle, the repeated lines. “Annunciation: Eve to Ave” suggests a sonnet—it contains fourteen lines, rhymed abba abba cab dea, with additional internal rhymes, and many of the lines are basically iambic pentameter. But some are not. The poem takes more liberties with the form as it proceeds. And those liberties are what I admire most; the poem overtly disrupts our expectations of form, just as the event it describes must disrupt any expectation of nature and human life. Szybist understands form thoroughly enough, she is comfortable enough within poetic tradition, that her poems pay homage to these forms and also extend them.

I have read Incarnadine numerous times, as one does preparing a review. Yet I sense that I am only beginning to comprehend its depth. I look forward to keeping these poems near, for what they can teach me about poetry, yes, but more for the pleasure I experience, each time, reading them.