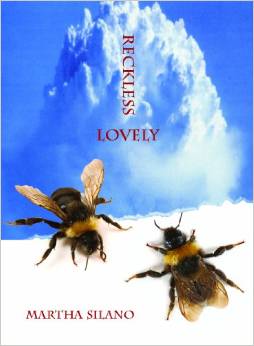

Martha Silano. Reckless Lovely. Saturnalia Books, 2014. 68 pgs. $15.00.

Martha Silano. Reckless Lovely. Saturnalia Books, 2014. 68 pgs. $15.00.

Reviewed by Lynn Domina

The most succinct statement I can think to make about Martha Silano’s fourth collection, Reckless Lovely, is that it is wildly imaginative. It’s the juxtapositions, the connections, the metaphors she creates that attract me so, and they are all entangled in a clash of language that compels the reader’s curiosity. There’s no nodding off in the middle of this book. Reading her poems, I’m reminded a little bit of Pattiann Rogers, a little bit of Barbara Ras, a little bit, even, of Gerard Manly Hopkins. Yet Silano’s voice is her own. The poems are reverent without being pietistic, irreverent without being mean-spirited; they are smart without being pedantic, studded with references to popular culture yet also engaged with large questions; they are fetching and feminist and downright funny.

Reckless Lovely is arranged in three sections, reasonably similar in length. Most often, the poems are composed in couplets, though the collection includes several other forms, including prose poems, odes, abecedarians, glosas, and others. There’s enough variety of form—including overlap or combinations of forms—so that the predominance of couplets seems an active choice rather than a default mode.

While there are many poems I would like to discuss, I’ll limit myself to two. (Regarding the others, such as “Ode to Frida Kahlo’s Eyebrows,” I’ll just thrust the book at you when we meet, saying, “Here, read this.”) Although these poems differ in form, they both exhibit Silano’s strategies and strengths in terms of poetic craft, and they both illustrate some of her interests in terms of content.

“Black Holes,” the second poem in the collection, is a prose poem that relies on extended metaphors and consistent patterns of imagery in its attempt to explain something that is, to many of us non-scientists, just too bizarre to comprehend even if we believe we possess a rudimentary understanding. A black hole is itself, of course, a metaphor, not a hole at all but a segment of space so dense, whose gravity is so strong, that nothing, not even light, escapes. To our human eyes, any space absolutely devoid of light appears to be empty. So many poets have used the phrase “black hole” simply as a metaphor, to the extent that its use as a metaphor has become clichéd, even though many people who seem to find the phrase attractive also seem to have little understanding of its actual meaning. Silano refreshingly (at least as far as I can tell), in this poem and others, gets the science right, although the poem has at least as much to do with daily life and human longings as it does with a scientific concept. The poem begins with an interesting explanation of a black hole’s characteristics:

Those pink splotches up there on the planetarium ceiling? What happens when fusion ceases and gravity wins, the lighter stuff spewing in all directions, winding up as craneflies and shrews, the big stuff collapsing, reducing down to a dark pumpernickel loaf the baker neglected to knead. Challah’s much less dense—light escapes. Same goes for Wonder Bread.

The poem continues this way, describing the human form in terms of pasta, mentioning Einstein, parking spaces, and Mick Jagger, incorporating technical language—“gravity is just the curvature of space and time” and “the point of singularity”—along with “Aunt Josephine’s eggplant parmigiana.” It all concludes with this elaborate sentence that both summarizes and extends the poem:

It reminds me of the summer I tried to learn a foreign language, feeling all wow, when really I knew about fifteen words: Por favore, un mezzo kilo di pane, and just like that—thwack of a knife, hunk of crusty bread—the same way I’m telling you now there’s no escape.

To catch on to what Silano is doing here, the poem requires rereading, but the language is so much fun that most readers, I imagine, would be drawn to reread it anyway. The poem rewards several readings, in fact, as allusions and images reveal the poem’s structural logic. We reach the last line again and again, acknowledging that there is no escape, not from the laws of physics and not from our human frustrations, anxieties, and desires.

“How to Read Italian Renaissance Painting” relies on equally interesting language. Written in couplets, it represents on the one hand many of Silano’s characteristic strategies. Yet it also reveals how adept she is with these strategies. She relies on parallel sentence structures and repeated phrases often enough to create insistence, but she also shifts the phrasing frequently enough to maintain readerly interest. Initially, the poem introduces features common to Renaissance painting:

Pay attention to the cryptic grapes, wandering

aimless skulls, a robed apostle’s vortex

of red. Pay attention to luminous gloom,

to the attention paid to each fold, each leaf,

each angel’s blue-tipped wing, to every look

of beseeching dismay. Notice uneasy clouds

to the right, uncertain urns to the left. Notice

theatrical expressions, God diving in to shatter

the silence in Mary’s room. Notice shutters

everywhere. Take these to mean the master

is a master of worry…

This repetition works because the structure of the lines does not simply duplicate the structure of the sentences. The repeated words “Pay attention” and “Notice” never appear in the same position within a line more than once. The rhythm of the poem, then, as the product of line and sentence, becomes much more interesting because Silano attends thoughtfully to both, composing as good poets do, according to the line. The meaning of lines, taken separately from the meaning of sentences, enlarges the meaning of the poem. For example, if we read the lines “theatrical expressions, God diving in to shatter” or “everywhere. Take these to mean the master” as lines rather than only as components of sentences, their meanings shift, sometimes slightly, sometimes more profoundly. Is God’s activity a piece of theater? Is the master everywhere, just as the shutters are? Of course not every line will function this way, but most of us could probably improve our craft by reading Reckless Lovely specifically to analyze how Silano uses the line.

The repetition in this poem also works because it’s not the only thing going on. Notice, for example, the assonance in “luminous gloom,” followed by “blue” two lines later. Then there’s “uncertain urns” in line seven. And there’s the alliteration of “shatter the silence” and “shutters.” And there’s the off rhyme of “shatter,” “shutters,” and “master.” In addition, the vocabulary is consistently concrete, and the parts of speech that tend to flatten out rhythm—prepositions, articles—occur rarely. Nouns and verbs predominate, but even the modifiers are interesting: “cryptic grapes,” “blue-tipped wing,” “beseeching dismay.” “How to Read Italian Renaissance Painting” is a finely wrought poem. It’s given me pleasure as a reader, for it’s encouraged me to think about the visual arts more carefully, and it’s given me pleasure as a writer as I’ve noticed how attentively Silano approaches craft.

Silano’s care for language is apparent throughout this collection. The content of her poems suggest that she is a poet with broad interests, which makes for interesting reading. Reckless Lovely is a collection I look forward to rereading.